First Year Writing Faculty Handbook

Copyright Jodie Childers

English 101 (Composition I) and English 102 (Composition 11/Introduction to Literature) are the gateway courses for all QCC students (Digital Art and Design and New Media Technology students take EN-103 in place of EN-101. These courses offer most students their first college-level practice in skills such as analysis, textual interpretation, and synthesis of multiple sources–all important skills for their future college success. In general, all faculty teach at least one of these courses every semester.

Here are the definitions of both courses from the QCC catalog:

EN-101; English Composition I (3 class hours 1 recitation hour 3 credits) Prerequisite: A score of 480 on the SAT, or 75% on the New York State English Regents, or a passing score on the CUNY IACT Writing and Reading tests. Note: Credit will not be given to students who have successfully completed EN-103. This course focuses on the development of a process for producing intelligent essays that are clearly and effectively written; library work; 6, 000 words of writing, both in formal themes written for evaluation and in informal writing such as the keeping of a journal. During the recitation (conference) hour, students review grammar and syntax, sentence structure, paragraph development and organization, and the formulation of thesis statements.

EN-103; Writing for New Media (3 class hours 1 recitation hour 3 credits) (This course is required in lieu of EN-101 for: A. A. S. Degree Program in Digital Art and Design (D. A. D. ); New Media Technology Certificate Program; A. A. S. Degree in New Media Technology. ) Prerequisite: a score of 480 on the SAT, or 75% on the New York State English Regents, or a passing score on the CUNY IACT Writing and Reading tests. Note: Credit will not be given to students who have successfully completed EN-101. Students will study and practice writing in Digital Media. They will concentrate on producing clearly and effectively written formal essays with the goal of learning how to communicate in the World Wide Web and e-mail environments. Particular attention will be given to the process of writing, including the use of informal writing strategies. Proficiency in standard grammar and syntax, sentence structure, paragraph development and organization, and the formulation of thesis statements will be stressed in the context of preparing essays, arguments, hyperlinked and other new media documents.

EN-102; English Composition II: Introduction to Literature (3 class hours 1 recitation hour 3 credits) Prerequisite: EN-101. Continued practice in writing combined with an introduction to literature: fiction, drama, and poetry. During the recitation hour, students review basic elements of writing; analytical and critical reading skills; and research strategies.

Although these are separate courses, we view them as if they had one continuous arc because, aside from a few transfer students, all of our students will take both courses at some point in their QCC education. One way of making connections between the two courses is to analyze and explore genre with our students. The catalog definition of EN-102 specifies a study of genre (at least fiction, poetry and drama), but this study should probably begin in EN-101. Although the essay is a mandated part of EN-101 (though definitely not the only genre permissible), students should be educated that the term "essay" is an umbrella term which shelters many subgenres such as the five-paragraph themes, summary, analysis, exploration, argument, reflection.

Students should learn, as both readers and writers, that the world of texts is a world of genres, of writing and reading "situations." Rather than teach the myth of the "academic essay" (again, an umbrella term that fragments and breaks down as we move across disciplinary lines), students should learn that part of writing is learning to meet reader expectations (or to challenge those expectations fruitfully.) As a result, students need to learn to read critically and reflectively, identify genre and rhetorical situations, ask fruitful questions of texts and imagine how they could insert themselves into the conversations that those texts engage. Lee Ann Carroll and others have shown in their research that it's unlikely that we have the ability to prepare every student for every single writing situation. Therefore, perhaps the next best thing is to have them read and write in as wide a variety of genres as possible, to make them aware that they are engaging in dialogue with other texts which share similar rhetorical moves.

It's true that, like most complex endeavors that involve multiple persons working toward one or more goals, teaching is inherently a sloppy enterprise. This, perhaps, is both its biggest boon and biggest shortcoming. However, we should probably put as much thought as possible into our teaching in order to make the hard work that takes place in a classroom pay off. The aim of this manual is two-fold: 1) to help both new and seasoned instructors conceptualize, rethink, develop, and execute their first-year writing courses at QCC and 2) to offer a set of "best practices," documents and assignments that our professors have created for their 101and 102 courses. Hopefully, this text will both help you in the creation of your own courses, while at the same time informing you about how we in the English department view first-year writing at Queensborough.

How to Use This Book:

We have compiled documents composed by several professors in this department to create this guide. Many of these documents are actual texts handed out to students (e. g. sample syllabi and assignments).

Good luck with your courses and please feel free stop by and speak with us at any time if you have questions or if you just want to share what you're doing in your classroom.

Best,

John Talbird, Writing Program Coordinator

Rob Becker

Jodie Childers

Beth Counihan

Jean Darcy

Mike Dolan

Joan Dupre

Barbara Emanuele

Laurel Harris

David Humphries

Susan Jacobowitz

Daniel Paliwoda

Linda Stanley, emeritus

We would also like to thank Bruce Naples, Executive Director of Academic Computing and eLearning, for the many hours he devoted to helping us to transpose the original paper version of our handbook into this digital format. And thanks also to Aradhna Persaud and Ashley Grant of the ACC who cheerfully helped with the technical and detail work.

Rolando Chavez "East River Arch Bridge" photo used with permission

The cliché is that the syllabus is a contract between you and your students. At Queensborough, it is required that every instructor distribute to students a complete syllabus at the start of each semester.

QCC Course Outline Template (suggested order only)

Any student who feels that he/she may need an accommodation based upon the impact of a disability should contact me privately to discuss his/her specific needs. Please contact the office of Services for Students with Disabilities in Science Building, room 132 (718) - 631-6257 to coordinate reasonable accommodations for students with documented disabilities.

General Education and Course Objectives for EN-101and EN-102

EN-101addresses the following General Education objectives of the college:

Course objectives/ expected student learning outcomes:

By the end of EN-101, students will be able to perform the following tasks:

EN-102 addresses the following General Education objectives of the college:

Course objectives / expected student learning outcomes:

By the end of EN-102, students will be able to perform the following tasks:

It's true that it behooves you to let your students know what you expect from them over the course of the semester. However, another reason for having a detailed syllabus is that when an instructor takes the time to craft a syllabus, that instructor is thinking about the class before it begins. The instructor is conceptualizing the what, when, how and why of the course.

A big part of syllabus-planning is concerned with simply giving students stuff to do, filling the time of each class day, filling a semester with activities. However, we feel that a course should have a forward movement rather than simply a bunch of activities. It should have a narrative.

There are numerous ways to create a narrative for a course. For instance,

Following the course descriptions for EN-101 and EN-102 are sample syllabi from our faculty.

Kareen Gibson "Friends" photo used with permission

Course Description and Objectives from the catalog:

EN-101; English Composition I (3 class hours 1 recitation hour 3 credits)

Prerequisite: A score of 480 on the SAT, or 75% on the New York State English Regents, or a passing score on the CUNY/ ACT Writing and Reading tests. Note: Credit will not be given to students who have successfully completed EN-103.This course focuses on the development of a process for producing intelligent essays that are clearly and effectively written; library work;6, 000 words of writing, both in formal themes written for evaluation and in informal writing such as the keeping of a journal. During the recitation hour, students review grammar and syntax, sentence structure, paragraph development and organization, and the formulation of thesis statements.

EN-101addresses the following General Education objectives of the college:

Course objectives/expected student learning outcomes:

By the end of EN-101, students will be able to perform the following tasks:

In addition to these explicit aims and scopes, there are also goals relating to the institutional designation of EN-101 as a Cornerstone experience. Cornerstone courses require students to demonstrate the following skills:

In EN 101, students work to acquire writing abilities and to develop a critical sensibility that will enable them to learn such essentials of writing as purpose, situation, audience, research, form, tone, and style. The focus is on learning to create effective texts in a variety of genres. Through the study of genre, students learn to see the connections between reading and writing.

Writing is a process in which all writers, experienced or inexperienced, can engage, and the stages of which inform the pedagogy of the course. This process includes generating a subject, generating ideas to develop that subject, organizing research strategies to further develop and support the subject, understanding the purpose and audience for which the writing is intended, making organizational and stylistic choices, and responding to self, peer, and/ or instructor critique by reevaluating, revising and editing.

Course Organization

Writing assignments are typically constructed across the semester to move from the personally expressive to the more objectively academic . We suggest unifying the coursework around a theme or themes such as " community" or "cultural difference ." The trajectory of the course may be seen as forming a narrative . A narrative/ thematic approach gives a specific context for reading, writing, and class discussion and encourages the construction of writing assignments that build on earlier ones.

In addition, we suggest an appreciation of genre not as a limitation of form but rather as a site of exploration that actively responds to variations within rhetorical, thematic, and social situations and considers the role that writing plays within such positions and contexts. Research is viewed not in isolation but rather as an ongoing process that engages methods of inquiry such as the scaffolding of assignments or the investigation of sources as steps that lead to and enrich completed projects.

Reading Assignments

Reading in EN-101should be closely aligned with the writing that students do. This can manifest itself in a number of ways: writing responses, in-class writing as precursor to discussion, more formal assignments that ask students to mimic/ adapt/ rewrite published texts, to name just a few. Reading assignments should also help control or focus the work of the semester. In addition to aiding students to get a handle on the content/ themes of the course, reading can help students to create a "narrative" for EN-101: if student readings are linked by a common theme or narrative, they can aid students in understanding how their own writing is linked by a common purpose (imagining an audience, envisioning their writing as "doing work" outside the classroom).

Some in and outside English studies dismiss first-year writing, and particularly the first semester of this sequence, as a "course without content." We contend that the "content" of English 101is writing. This does not make reading secondary, however. Although studies are inconclusive about whether "good" writers must necessarily be good readers, one thing is not debatable: writers need readers. As a consequence, writers must be readers in order to know what readers want/ need.

As a way toward discussing readerly concerns, this study of texts should involve an ongoing discussion of genre. Rather than general labels like "essay" (for reading assignments) and "paper" (for writing), we encourage instructors to aim for exactness and help their students realize that all reading and writing in the English language is a part of a long history of texts and of a wide continuum of genres and writing/ reading situations. The only way we--as readers, writers--know how to identify any kind of text is by comparing it to other texts we've read and written. For this reason, we urge instructors, whenever possible, to use specific generic terms like "analysis," "memoir" and "narrative" in addition to more general ones like "essay." That said, nearly any reading assignment imaginable can "do work" in EN-101: the exploratory essay, literacy narrative, personal argument, news article, letter, fiction, poetry; how-to instructions, reflective musings, script--and even non-print sources like film, television, advertising and music, to offer a very short list.

Writing Assignments

Students who pass the course will be able to produce texts that reflect a clear thesis logically supported by details and examples; show an understanding of the logic of arrangement (cause and effect, comparison, definition, process); use appropriate vocabulary; and have a sufficient command of standard grammar, punctuation, and spelling to ensure reasonable clarity of expression. In addition, students will be able to analyze published essays and respond to them in well-organized essays of their own, citing relevant research and quoted, summarized or paraphrased portions of the published essays with in-line citations. (See section on the research component below. ) Students will be able to demonstrate these skills not only in revised and polished texts, but also in texts written in class within a limited amount of time.

Students will write a minimum of 6,000 words through a series of purposeful writing tasks, including both formal essays and various other genres as well as informal writing (journals, "free writing, " letters, short responses) or more focused writing exercises to teach a specific skill (such as summary or paraphrase). To prepare students for essay exams that they will do in other classes, instructors are required to assign a final exam (see below).

At least half of students' writing will be evaluated by the instructor. The 3, 000 words may be in the form of four 750-word or six 500-word formal texts or in some other similar combination, and one of these assignments will be written in class. These texts should have some sort of logical narrative progression (generally from the expressive to the analytical), and as a group, the writing assignments may be organized (at least loosely) around some central idea or theme, so that the second and third essays build on what the student has written before. Students should be taught to write multiple drafts and to revise and edit their formal essays. Students should also be taught to organize, write, proofread, and edit within the limited amount of time of an essay exam.

The Research Component

Research should be a constant and inextricable component in the training of writers. Throughout the semester, research should be a taught as a fundamental component of communication. Rather than limiting students to a single, long research paper (often relegated to the end of each semester), the instructor should ask for research and documentation in the writing assigned throughout the term. In addition, students need to be made aware that "research" is not limited to hunting for "information about X" in the library or online, but is rather a way both of looking at the world around them, and also one in which they are active and creative contributors to knowledge-making. Instructors should also structure writing assignments to incorporate references both to texts discussed in class and to outside source materials. Students should be asked to cite their sources on the EN-101final exam.

This research component--built into most if not all writing assignments given in a semester--will help students learn to value research as a relevant way to develop their own ideas within any discursive situation.

Research activities, which may or may not result in a formal text, should include finding, evaluating and collecting information from reliable sources—in the library, on-line, as well as from members of the community. An instructor who gives more emphasis to personal experience may ask students to incorporate research into their writing in the form of interviews, observations or surveys. An instructor may also encourage students to explore alternative source material including new and old media, films, museums, and graphs and charts. Because such alternatives to traditional research may be new to many students, a good deal of guidance in doing the research (and reflecting on the process of doing that research) should be incorporated into each course).

Expanding the idea of research can also mean enlarging the range of textual representations from summarizing, paraphrasing, documenting with parenthetical references and creating works cited pages, annotated bibliographies and literature reviews, to more non-traditional forms of research such as visual images and electronic, networked media including audio and video.

The Conference Hour

Of the four hours that the class meets each week, three are for classwork and the fourth is a "conference" or workshop hour for which activities are to be planned that focus on specific writing strategies and capabilities. These activities may include peer critiquing or other group work, sentence combining, freewriting exercises, or other ways of developing writing competencies.

Syllabus and Assignment Schedule

A course syllabus and assignment schedule must be distributed to each student at the beginning of the semester. Writing assignments should be fully developed, clearly and completely explained, and distributed in written form. (SEE COURSE OUTLINE TEMPLATE)

Description of the EN-101 Final Exam

Students will take a final exam, a text that they will compose in one or more classes. The exam will require students to reflect on course readings, class discussion, and / or supplementary material, and to develop a clearly-stated idea using relevant material from coursework and /or research. The final exam grade will count for a significant portion of the student's overall grade for the course; a suggested range for weighting is between 15% and 25% of the course grade. Every instructor will design an exam that addresses the way he or she teaches EN-101 and will use the departmental rubric:

EN-10 1 Final Exam Rubric

Lisandro Vargas "Showtime" photo used with permission

At the heart of the educational process are the opportunities provided for students to demonstrate understanding and knowledge in each of their courses and to have their command of subject matter evaluated by faculty. Students must be guided, therefore, by the most rigorous standards of academic honesty in preparing all assignments and writing all examinations. In cases of doubt about ethical conduct, students should ask their instructors. However the following rules apply in all cases:

These rules will assure probity in student evaluation and performance standards that are equal for every student enrolled in classes at the College. Any deviation from the aforementioned rules may result in a failing grade (F) for the work in question and for the entire course at the discretion of the instructor. More serious penalties may result in those instances in which the University's Student Disciplinary Procedures stated in the handbook are invoked.

It is very important that students attend every scheduled class meeting of a course.

Attendance is monitored from the first day a class is scheduled to begin. Absence from class can seriously reduce the student's chances of completing a course successfully. Generally, absences beyond 15 percent, or excessive lateness, may result in failure in a course. However, students should consult instructors for individual course requirements. For information on students' rights and privileges in regard to attendance on certain days of religious observance, please see the Student Regulations section of the QCC catalog.

Copyright Jodie Childers

Click links to view syllabus examples:

Talbird Syllabus

Paliwoda Syllabus

Harris Syllabus

Billy Jno Hope "Salsa on 14th St" Photo used with permission

The pedagogy of surprise is what happens when you ask your students to describe the one specific moment or event or person that brought them to this particular place, in your classroom, and to find themselves traveling in this world.

The pedagogy of surprise is an acknowledgment that the very students who have been processed by years of high-stakes testing are ready to respond at the first opportunity to lowstakes writing.

The pedagogy of surprise is what happens when you walk into a writing classroom at a place like Queensborough Community College and listen.

The pedagogy of surprise is what it means to think of teaching and learning as an everyday experience.

The pedagogy of surprise is a play on Paulo Freire's pedagogy of the oppressed--respectful play.

The pedagogy of surprise means interacting with students as critical individuals not as empty vessels waiting for deposit. The means of banking is digital and the means for breaking the banks is digital as well.

The pedagogy of surprise is what it means to consider language as a virus and language as a way to heal, to consider language as the patois of the young and the artifact of all ages. It is to wonder what Emerson would have texted.

The pedagogy of surprise is what it means to recognize the fullness of the moment, as in a poem, and to recognize that experience can be integrated into a whole, as in a novel.

The pedagogy of surprise is to recognize that writing is a process, but the result is not processed. It is a pause on the way to somewhere else.

Georgiana Seetaram "Subway Stop" Photo used with permission

An Introduction

When I began my job at QCC as Assistant Director of the Writing Program, I decided that my first semester on campus, to better get a sense of the pedagogical culture of the first-year writing (FYW) program, I would use the same textbook that the majority of other faculty used in teaching EN-101. I hadn't used a textbook in many years, in fact, since my first couple of years of teaching. The Ph. D. program I attended required that new graduate student instructors assign trade books for course texts (a list of possible books to order was distributed before the semester began). No college textbooks were allowed. I don't know if there was a theory behind this prohibition--probably, though I don't know that it was ever communicated to me. I adapted. And then, later, when I came to QCC and saw that many instructors were using a textbook, I ordered the same book without much thought.

Except that I had changed. How to assign reading from a textbook, which has more texts than any sane, non-sadistic professor would assign in a normal semester? Which ones do you choose? How do you organize the readings? Do you simply set them up thematically; using the same ready-made themes/units that every college text seems to come with? In my very first semester of teaching--actually assisting a more experienced instructor teach her course--a college textbook was used, the course units were the textbook's units, even the writing assignments straight out of the textbook. I didn't know much about teaching then, but I sensed that a prof who took everything from a textbook was giving away something crucial in the design of a course.

Although I struggled in writing my syllabus that first term at QCC, the theme of the first unit for that course was easy to design: the literacy narrative. Peter Gray; a QCC colleague, had written a brief description of the literacy narrative in the textbook-- essentially a story; memoir, having to do with one's acquisition of reading and/ or writing skills, although Pete raised the possibility that " literacy" could encompass other realms--and several of the readings: Sherman Alexie's " Superman and Me ", Amy Tan's "Mother Tongue." and even an essay by former student (and current QCC administrator) Susan Madera ("One Voice") were model literacy narratives.

The Literacy Narrative in First-Year Writing

The literacy narrative is an ideal genre to get students to read and write at the beginning of EN-101. Many enter our classrooms thinking they're bad writers, that they know very little that is valued in college, and that they'll never "know grammar" (see here for what John Bean has to say about this and also the " politics of grammar " (pp. 69-73)) They've been judged, many of them, as poor writers. The literacy narrative can be empowering for many of our students because they come to college thinking they're empty vessels that need to be filled up. The literacy narrative challenges this assumption because students bring into the classroom all they need to write one: their experiences. They're already an authority, they're the authority; the literacy narrative recognizes that they are already writers, even before the first day of class. But the literacy narrative isn't "just" a personal story; it's more than "what I did over the summer." It asks students to do many of the tasks that the academy values: construct a narrative, reflect on learning, discover and articulate what's important, make convincing generalizations based on the facts, and complicate the familiar. As Mary Soliday has written , "By foregrounding their acquisition and use of language as a strange and not a natural process, authors of literacy narratives have the opportunity to explore the profound cultural force language exerts in their everyday lives."

Why I Stopped Using a Textbook

That first semester at QCC, I discovered that a student who was doing well otherwise in the course was failing all his reading quizzes. When I asked him why he wasn't doing the reading, he answered that someone had stolen his textbook and he couldn't afford to buy a new one. As I have too often, before and since, I shrugged this excuse off. He could have gone to the library to read the one on reserve, he could have photocopied the relevant reading from one of his classmates, he could have found many of the readings online or in the library for free, etc. However, somehow, I couldn't get a nagging feeling out of my head every time he handed back a blank quiz with a shrug and a rueful smile.

I realized I didn't know how much the text cost, so I went across the parking lot to the bookstore to find out. I was a little shocked to realize that that thin textbook I'd been requiring all my students to buy was over eighty dollars. Although I was finding that the textbook bored me and my students and I probably wasn't going to use it again, after discovering its prohibitive cost (which, in hindsight, I probably should have known), I decided to drop it and return to using trade books. Since I had had a lot of success requiring the literacy narrative, I decided to continue to copy and distribute a few essays that I had used from the textbook or other sources.

And Why I Ultimately Stopped Requiring a Literacy Narrative

I give my students a lot of time, especially early in the semester, to write in class (this is great practice in a computer class, since students can draft for a more formal assignment, but even useful in the more traditional classroom using pen and paper). Since I want students to know that I take this work as seriously as I hope they do, I often write with them (also, if I don't write, I find myself getting antsy and stop the in-class writing too soon). As I wrote my own literacy narratives, I discovered something crucial about my own learning: Being a student made me love books. I'm not just talking about the stuff inside books--the ideas and metaphor and play of language, etc.--but the actual books themselves, their covers and pages (especially when they're new, but also when they're used and in an edition that most others in the class weren't reading). I had seldom bought books before then- mostly reading books from the library or from my parents' collection or loaned from friends--but I loved buying my books at the beginning of each term, the feel of them, especially when I found them used, in near-mint condition.

I should be specific: This time that I'm describing is when I was a junior and had decided on English as a major (after bouncing around from Journalism to Advertising to Psychology to Math) and I was firmly ensconced in the major and no longer using textbooks. Although I wouldn't have had the language to describe it (having not yet taken an Existential Literature or Philosophy class), textbooks were alienating to me. They were heavy and they were boring. And they were so very expensive.

This is not to say that trade books are cheap, or were even then. I was a student financing his education on Pell Grants, student loans, and too many hours at a falafel joint. But trade books offered a sense of excitement for me as a student. The big stack of books that I carried to the register at the beginning of every term felt like potential. I never felt anything but tired when I had to carry my standard college textbooks to the register--and then sorrow when I got the bill. I feel that excitement now when I'm designing my course, composing writing assignments, choosing my texts. It feels, in those early days, that anything might be possible.

That memory of early-semester excitement as a student made me return to assigning texts again, trade books, real books, the kinds of books one finds in a real bookstore (as opposed to your typical campus bookstore, which is made for anything but browsing). Rather than assign photocopies (because, though a photocopy may be free/ cheap to use, when is the last time you were excited about being given one to read?), I began ordering trade book literacy narratives: The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Bootstraps (Victor Villanueva), Lives on the Boundary (Mike Rose).

But just as it's difficult to read the same book over and over, it can be tiring to assign the same book for the same class too many times. Recently, I've started assigning The Best American Essays series (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) to create variety in my EN-101experience. The Best American series is generally full of autobiographical writing, many of the essays are written by some of our best writers, and some texts are even literacy narratives (for instance, "Rude Am I in My Speech" by Caryl Phillips from a recent edition (2011)). This series, I have found after reading it for several years, has complicated that term "essay" for me. Although many of us in the academy value that genre--especially in the Humanities, but in other disciplines too--as WID /WAC Coordinator for several years, I've come to see that it means different things to different people depending on their discipline or background. In fact, it would be more accurate to say that it's an umbrella term, encompassing autobiography, pop culture analysis, political rant, social issue exploration, investigative journalism, etc. One type of essay that every Best American has in multiple styles and varieties is the personal essay, which is really all a literacy narrative is, though a personal essay focused on a specific subject matter.

And perhaps that specificity was what made me veer away from assigning the literacy narrative. Back when I used to first teach trade books in FYW during my Ph. D. days, I used a portfolio system (another requirement of that FYW program) and let my students write about essentially anything they wanted to. I got a lot of stories about dead grandparents and big football games and prom dates. Some of my colleagues outlawed these topics-- much in the way I've heard some outlaw certain well-worn social issues like abortion rights and gay marriage--but I felt that any topic could be made fresh again. (How can any English professor not think that after reading Shakespeare's repurposed folktales, Joyce's updated classics, and Angela Carter's revisionist fairytales?) I still believe this and Best American is a good example of how many well-traveled narratives can be made new again. In that recent edition there is a coming-out story written as a hybrid prose poem and pop culture analysis (Hilton Als' "Buddy Ebsen"), an argument for a revision of our current healthcare system disguised as a personal essay about the death of a parent; Katy Butler's " What Broke My Father's Heart"; and a film review that turns into a critique of Facebook--and simultaneous examination of the Millennial Generation (Zadie Smith's "Generation Why?"). All the essays, despite their various approaches and aims, use the first-person narrator (except one, Madge McKeithen's "What Really Happened" an essay about the murder of a friend written in the form of directions (2nd person), a how-to on navigating the North Carolina prison system).

I find that Best American keeps EN-101 fresh for me; it keeps me on my toes. It's like when I give part or all of a class up to small group work: I'm relinquishing some of the control of what this course can be, I'm Jetting my students (in a way) design the course with me. Though I'll have read the book at least once before the semester begins, when I reread it with them, I'll be in the process of experiencing it with them.

But there are any number of ways of teaching the literacy narrative or the personal essay; this is just the way I've come to it (and it's still a work-in-progress, always will be; this is just where I am now). You may have your own way (or your argument for why the personal essay is not a good first assignment in FYW). Hopefully, you will want to join in the conversation and contribute your assignments and text suggestions to the department database.

Despite the personal nature of autobiographical writing, students do need help getting started. Below, please see some invention activities along with a couple of assignments and suggested readings.

To see these documents, please visit the department archive.

Alexie, Sherman. "Superman and Me." LA Times 9 April, 1998.

Atwan, Robert. Series Ed. The Best American Essays. (Multiple Years.)

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas. Dover , 1995 .

Ehrenreich, Barbara. Nickel and Dimed . Picador , 2011.

hooks, bell. Bone Black. Holt, 1997.

Jordan, Teresa. Riding the White Horse Home , Vintage , 1994 .

Karr, Mary. The Liar's Club . Penguin, 2005 .

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior . Vintage , 1989 .

Mairs, Nancy . Plaintext . U of Arizona P, 1997.

Ma lcolm X. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. (as told to Alex Hailey). Penguin, 2001.

Tan, Amy." Mother Tongue."

Miller, Henry. Plexus . Grove, 1994.

Prejean, Sister Helen. Dead Man Walking. Vintage , 1994.

Reitman, Dr. Ben L. Sister of the Road (aka. Boxcar Bertha). AK P, 2002 .

Rose, Mike. Lives on the Boundary. Penguin, 2005.

Thompson, Hunter S . The Great Shark Hunt. Simon & Shuster, 2003.

Villanueva, Victor. Bootstraps: From an American Academic o f Color . NCTE, 1993.

Wolff, Tobias. This Boy's Life . Grove, 2000.

Alexander, Kara Poe. "Successes, Victims, Prodigies: 'Master' and 'Little' Cultural Narratives in the Literacy Narrative Genre ." CCC 62. 4 (June 2011): 608 - 633 .

Bean, John C. Engaging Ideas: The Professor's Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking and Active Learning in the Classroom . 2nd Ed. Jossey-Bass, 2011.

(Available as an e-text through QCC's ebray link ) .

Dewey, John. Democracy and Education . Simon & Brown, 2012 . Digital Archive of Literacy: Narratives . OSU.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed . Continuum, 2012.

LeCourt, Donna. "Performing Working-Class Identity in Composition: Toward a Pedagogy of Textual Practice." College English 69. 1 (Sep 2006) : 30 - 51.

Soliday, Mary . "Translating Self and Difference through Literacy Narratives." College English 56. 5 (Sep. 1994): 511-526.

Schrader, Claudia. " The Power of Autobiography." Changing English 11. 1 ( March 2004): 115-124.

Copyright Phillip Roncoroni "Ideas are Bullet Proof: Occupy Wall St"

We return to the archives to see for ourselves what has been left out, to retell the story, or to see the traces of a life, a historical event, an institutional history. What if we were to teach research writing through involving our students in the process of archival exploration? What if we were to invert the research process so that the task would not be one of synthesizing secondary sources, but, rather, one of contextualizing the primary sources simultaneously remembered and forgotten in the boxes of the archives? Bringing students into the archives can emphasize the organic and experiential, even the auratic, qualities of research. There are a wealth of digital archives that can be used in the writing and literature classroom. Online literary archives such as the Walt Whitman Archive and Modernist Journals Project and historical archives like John Jay's Crime in New York, 1850-1950 and Old Bailey Online, 1674 -1913 offer a treasure trove of primary sources to be interpreted and analyzed. However, my classroom project is a work in progress designed to make the dustiest of literacies--navigating physical archives--visible through online spaces, in the process offering our first-year writing students new possibilities for constructing and representing knowledge.

This project, still very much in-progress, was developed over two semesters through a partnership with the Queensborough Community College archivist Connie Williams . It involves community college students in the first-year writing classroom in the historiography of our college. My central goal through this process is to position students as interpreters of resources that have received little contemporary attention beyond the archives. In this reconstruction of the research paper, a genre generally relegated to the first-year writing program, I begin with the gap not only in my students' knowledge, but also the broader gap in campus and community knowledge, conduct background research, move into the archives, and, finally, reflect on the experience.

While I believe that research skills are one of the most important things I teach in first-year writing, I have long struggled with assigning the traditional research term paper, what Robert Davis and Mark Shadle call the "modernist term paper" with its "ideals of expertise, detachment, and certainty" (418). Nevertheless, I have found that the large-scope research project promotes crucial habits of mind. From the perspective of someone trained in literary research, I still maintain that research enables readers to enter the room and join the conversation to use Kenneth Burke's famous metaphor, promoting living in and through texts, becoming part of them. This is how research differs from search, which involves simply finding information while research requires sifting, interpretation, and synthesis. The Internet, I believe, has largely transformed the "modernist term paper" into an empty exercise, an invitation to right click plagiarism at worst.

The question becomes how to preserve key aspects of what we might call the traditional (as in early twentieth-century) research paper--participation in a larger academic conversation and information literacy--while making the work meaningful, not merely a formal exercise. Davis and Shadle call for a research process that values "uncertainty, passionate exploration, and mystery" (418). My theory in designing this project was that our campus archives might offer a rich repository for this focus on inquiry over mastery.

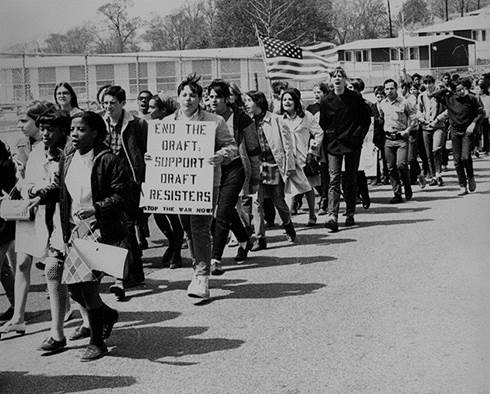

QCC Archive Photo, 1969 - Student War/Draft Protest March

I constructed this project using the college archives while teaching an English 101, introductory composition, course in a Learning Community, or shared class, with Sociology. In the Sociology section, students focused on texts about social unrest. In the English course, we applied this theory to student rebellion in the 1960s with a specific focus on a student occupation of the Queensborough administration building in1969, one of a series of student takeovers across New York City campuses in the spring of that year. While there were numerous articles that addressed this particular action at Queensborough in 1969, through the early 1970s in publications such as the The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The AAUP Bulletin, the only contemporary mentions I could find to bring to class appeared (very briefly) in Rick Perlsteins Nixonland (2000) and a chapter in former left-wing Queensborough history professor turned right-wing activist Ronald Radoshs memoir Commies (2001).

I will quote, with permission, a summary of what happened in 1969 on our campus from one of my student's papers: "A climb in tuitions and the removal of an English professor triggered a riot . . . The dismissal of Dr. Donald Silberman [allegedly for his leftist activism]. . . started it all. By 1969 roughly 8, 000 students attended QCC, and amongst them 50 pupils began a sit-in on the fourth floor of the administration building. Professor Silberman along with two of his coworkers, Professors Faigelman and MacDonald, joined them. The 50 pupils transformed into 300 striking students...[They] succeeded in that they made history, but failed because [50] students departed to jail and were kicked out of school. The professors were deprived of reappointment."

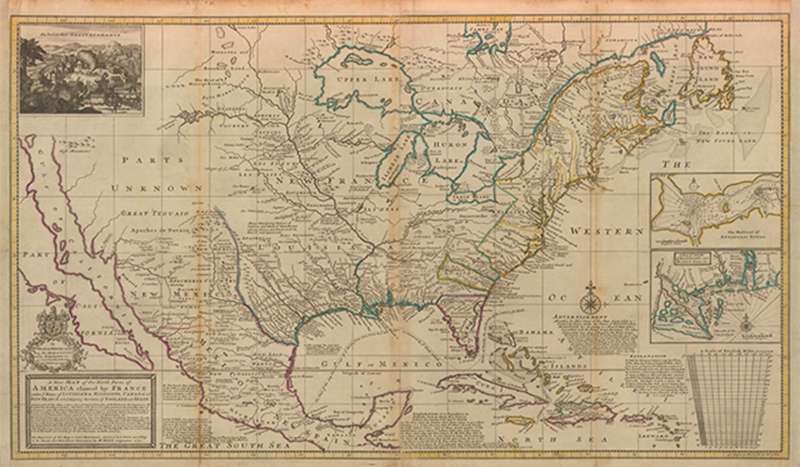

Such an action, specific to the Queensborough campus, had to be contextualized with student revolts that spring across other New York City campuses, (including Brooklyn College, City College, New York University, Fordham, and Columbia), for a multitude of reasons, including protested tuition increases, demands to admit more local students and students of color, and the push for black and Latino studies departments and research centers. We also considered the larger national context of student unrest, focusing on the Students for a Democratic Society's 1962 Point Huron Statement, the 1964 Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, and Angela Davis's 1969 firing from UCLA. After watching films and reading about these events in class, and writing informally in response to each text, students came up with their own research questions in groups in preparation for their visit to the college archives, including:

With these questions in mind, we visited the college archives, housed in the bowels of the library, over one week in two 100-minute sessions. In the first session, archivist Connie Williams gave an introduction to using the primary sources. Then she set the 25 students free in the archives, a tight, cool room full of boxes with an entire wall of old yearbooks, newspapers, course bulletins, and literary magazines on one end. In their reflections many students cited this as their favorite part of the project. They pulled the boxes labeled QCC Riots off the shelf and stacked them on the carts, then searched for other relevant materials including course bulletins, yearbooks, and newspapers from the period. Tightly packed back in another room around a long table, students began searching for the answers to their questions and formulating new questions, marveling at a yellowed sign protesting the institution of tuition and pouring through copies of the College Board hearing on the campus action. In their reflections, they acknowledged both the tedium and sense of discovery inherent to archival research. More than one student described it as being a detective. Their reflections expressed engagement in exploring the archives but considerable frustration in the search itself. Some students, hoping to find the answer key that eluded them in the boxes, told me that they had turned to the internet, especially Wikipedia, seeking some meaningful synthesis of this event that they could hook their ideas onto. Such a synthesis is not available online. One student asked the archivist if there were a book, an institutional history of Queensborough, available that she could read to contextualize her research. "There isn't a book about this history of Queensborough. You're going to have to write it," Prof. Williams replied.

This project took place over seven weeks. At its conclusion, students submitted portfolios that collected the following: ten one-page reflections and reading responses, ten pages of handwritten notes from the archives, at least three photographs or copies of archival artifacts, and a paper of at least five pages that summarized the events, offered a close reading of at least two archival artifacts in that context, and concluded with a reflection on how the Queensborough campus had changed since 1969. These tasks were constructed to incorporate expository, ethnographic, and reflective writing into a research project that would have meaning beyond the first-year writing classroom, showing students both the value of original research and the rhetorical complexities of making the past visible and meaningful.

The majority of the reflections evidenced student engagement in the experience of visiting the archives to "see for ourselves" while citing the difficulty of the assignment. Most of the students essays followed a progress narrative in which students in the 1960s had fought for their rights, which were now established as "We got change, " although a few connected the events of 1969 to student arrests at Baruch College that fall. While I think there is value precisely in the obscurity of this event, a history waiting to be written, balancing the basic demands of the project with a more sophisticated construction of meaning will be a next step, one which might involve an entire semester rather than half a semester. However, judging from the portfolios and reflections, this project did help students understand research more organically as the filling of a gap and more socially as a collaborative effort to curate, contextualize, and interpret a community's past. Sifting through local archives enabled students to experience research as a social, situated practice as opposed to a textually-based practice that primarily involves synthesizing the work of experts. We now need to work on connecting this past to our present.

Arguments making this connection might be forwarded through photographs, films, interviews, and sound recordings as well as through text. In its next iteration, we intend to move students from searching physical archives to constructing online archives, a process which might also transform from the argument-based research paper to other rhetorical modes such as description and narration as we consider audience and purpose.

I still have many questions around this project as it continues to develop: Which platforms would work best for presenting and contextualizing archival artifacts? How does a focus on what archivist Peter Carini calls "information literacy of primary sources" correlate to the web based literacies it is crucial for our students to develop? How can the second iteration of this project best be constructed to forge and reflect on this link? I end with questions rather than answers, reflecting the ethos of this project as one of inquiry and uncertainty.

To find a lesson plan, bibliography, and other materials, please click here.

Copyright Jodie Childers "Main St Flushing"

Over the past decade, Professor Jan Ramjercli and I have developed an alternative mode of teaching Freshman Composition, one that takes seriously and builds upon our students' existing knowledge, interests, and experiences. Ethnography is the written study of human culture from the insider or participant viewpoint; although based in the discipline of anthropology, ethnographies are used widely in the health professions, social sciences, and in many other fields. This cross-disciplinary writing curriculum is focused on the study of the local cultures of Queens and uses ethnographic research and writing methodologies in a series of coordinated project-based assignments. Throughout the semester, students build the skills needed for the culminating project, a 10-page study of a student-chosen subculture of Queens. Course texts are Conformity and Conflict: Readings in Cultural Anthropology, an introductory anthropology textbook, and Fieldworking: Reading and Writing Research, which is an ethnography-based composition textbook. I also give students a booklet of sample student papers which provides models for the different ethnographic paper assignments. Original research generated by the students forms the basis of all their writing in the class.

Students quickly become interested in, and adept at, ethnographic methods, including observation, interviews, and taking fieldnotes, informal handwritten notes generated at the cultural sites of their choice. As students practice rigorous academic research and writing that relates to their own experiential knowledge of the diverse cultures of Queens, they are engaged in the subjects, their writing confidence increases, and they build the abilities to generate and organize ideas.

As outlined in the assignment sequence below, the course consists of a series of four ethnographic writing assignments, each focused on some aspect of culture: place, language, and ritual. The final paper is a research study of a subculture that uses ethnographic techniques learned in the three smaller papers. The audience for the papers is both other students and the professor, and one wonderful aspect of this method is that the subjects are both constantly new and generally interesting to other readers. Students write about the places and people in our shared environment of Queens, and past topics include the Hispanic "Quinceneara" celebration, the working lives of New York City policemen and taxi drivers, and the sub--culture of Mexican day laborers at a local Home Depot. Preparation for the ethnographic work includes the introduction of key terms- ethnography, culture, subculture, ethnocentrism, informant, and objectivity -- practicing interview techniques, and learning how to do effective library database research. Students write about their own membership in subcultures and they read both published ethnographies and their peers' papers. Most importantly, the students write: 60 pages of handwritten fieldnotes and a minimum of 23 typed pages (not including first drafts) are required during the semester, not counting homework and in-class writing tasks. By the end of the semester, students have gained a great deal of facility in both formal and informal writing, skills that will serve them well both at college and in their chosen careers.

Copyright Johannes Burgers "Winners"

I do a research stimulation exercise during the last third of the semester. By this point students have written three essays, narrative, compare/ contrast, and expository / argumentative, each with a draft. As such, they have learned many of the foundational elements of writing a research paper. These skills are brought to bear on a long term research project in which students have to write a research report on the best way to combat human trafficking in their pre-assigned country or region.

After watching the documentary Not My Life about human trafficking, students provide a list of top choices for selecting a country to work on. Depending on their performance in the previous part of the semester they are sorted into even groups. Thus, if a student would like to work on the US and has done really well, he or she gets that choice. If, however, the US group is already full and a student has not participated well, she will get her second or third choice.

From the day I distribute the assignments and the supplementary materials, the classroom functions like a real world office with several assignments concurrently. Students are required to plan their days accordingly. At the beginning of each class, each team is required to have a member give a status report; it must be provided by a different person each class.

This is to make sure everyone presents. The larger assignments are provided through memo format and students must use their critical knowledge to figure out what the format of the assignment is. There is little to no explicit explanation, though I do provide feedback if students ask for it. This is to encourage them to figure out assignments for themselves. Along the way, I provide mini-instruction and models on specific elements required for the report. Hence, if citation is required I will explain the citation system we are using and why we are using it. They then have to complete an assignment based on this. The primary skills I teach them during this section are evidence-based, and include database searching, information hierarchies, and integrating external information through citation and paraphrasing.

Throughout the project there is also a team reward system. Basically, teams are judged on the performance of their entire team. If a student shows up late, texts, sleeps, or, in general, acts unprofessional, I will deduct points. On the other hand, if a team shows initiative, thinks outside the box, collaborates, or does anything else meritorious they will be rewarded with extra points. The team that wins at the end of the semester will be rewarded with significant bonus points.

A complete section of materials can be found here .

Copyright Jodie Childers

EN-102; English Composition II: Introduction to Literature

(3 class hours1recitation hour 3 credits. Prerequisite: EN-101. )

Continued practice in writing combined with an introduction to literature: fiction, drama, and poetry. During the recitation hour, students review basic elements of writing and analytical and critical reading skills and research strategies.

EN-102 addresses the following General Education objectives of the college:

Course objectives / expected student learning outcomes:

By the end of EN-102, students will be able to perform the following tasks:

Objectives

In EN-102 students are introduced to the study of literary texts and explore, in discussion and writing, informed ways to respond to the reading of such texts. Assignments should familiarize students with the major literary genres-- fiction, poetry, drama--and may include other genres and media as well. EN-102 should continue reading, writing, and critical thinking practice begun in EN-101. EN-102 makes use of a wide range of texts to examine how and why literature is created and why it matters.

EN-102 has been designated as a Milestone experience. Milestone courses require students (usually in the form of an assignment or group of assignments) to:

Organizing the Course

Writing. In addition to reading assignments, students in EN-102 practice their analytical and critical thinking skills through a variety of writing activities, such as a reading journal, writing in or out of class, taking exams and quizzes and completing projects that incorporate research. These are meant to encourage student engagement and effective communication. Writing assignments should foster close reading of texts, reinforce literary concepts and critical approaches, and enhance students' analytical, creative and interpretive abilities. Students should write a minimum of 6, 000 words, incorporating both low-stakes and high-stakes writing assignments. A minimum of 3, 000 words should be evaluated by the instructor.

Reading. Texts will include fiction, poetry and drama and may include other genres as well. There should be an organizing principle (thematic, genre, conceptual, historical) guiding the course, and EN-102 should promote reading and writing skills and provide preparation for advanced and elective courses.

Exams. At the end of the semester, students should take a final exam during final exam week. The exam should give students the opportunity to respond in writing to the reading they have done during the semester.

The Conference Hour

Of the four hours that the class meets each week, three are for classwork and the fourth is a "conference" or workshop hour for which activities are to be planned that improve student reading and writing skills that achieve the objectives of the course. These activities may include peer critiquing or other group work, freewriting exercises to improve fluency and generate ideas for discussion and/ or more formal writing, library research, and conferences with individual students or with groups.

Course Syllabus and Assignment Schedule

A course syllabus and assignment schedule must be distributed to each student at the beginning of the semester. Writing assignments should be fully developed and distributed in written form.

Copyright Jodie Childers

Click on the links below to see examples of EN-102 syllabi:

Alves Syllabus

Izzo-Buckner Syllabus

Lau Syllabus

Writing and reading are interconnected skills. There is voluminous research showing the connections, but it's also common sense. Writers learn to put together texts by reading. They learn what they expect as readers, what they like and admire, how to supply those qualities in their own texts. They imitate. They borrow - or as T. S. Elliot said, they steal. They build their vocabularies, complicate (or simplify depending on the need) their syntax, reveal the complexity of thought in action. Conversely, readers learn to be better readers by writing. They begin to understand the way texts are put together. The myth of the writer in his garret (too often "his") begins to disintegrate as they discover the steps (and missteps and sidesteps and resteps) of writing. They understand that subtext--the mythical "secret message" of English literature courses--is something that every text has, that it's up to the author to decide how complicated or simple that subtext should be, and ultimately, that subtext (or, more specifically, meaning) is something that writers and readers collaborate to create.

In our department, we believe that texts are more than just a vessel for content, that reading assignments are more than simply catalysts for class discussion. In order for students to see real connections between reading and writing, we feel that reading assignments should be read rhetorically (i. e. they should be dissected so that students can see how they work, not just what they say). We also feel that writing assignments should directly address the reading that is done in a class. In addition to having students "write back" to the texts they read (via journal, informal response, Blackboard, etc.), they should be encouraged to "steal" rhetorical strategies from the readings.

Copyright Jodie Childers

Following is a selection of reading and writing assignments from our faculty that we feel illustrate this spirit of writing and reading.

Below, please follow the links to some sample writing assignments (some with annotations in italics). To see a wider range of approaches to writing assignments in 101and 102, please check out the departmental archive .

101 : Arts of the Contact Zone

101 : Ethnography- Assignment

101 : Walking Tour Assignment

102 : Antigone Assignment

102 : Research and Writing Fiction

It has become common knowledge in the discipline of English (if, unfortunately not all disciplines) that the lecture model, if not exactly a "bad" model, is one of the least effective approaches to teaching. Another common truth in our profession is that different students have different learning styles. And finally, we all (at least, now, in this mass-mediated age, but probably since forever) crave at least some variety in our experience, and in the classroom is no different. Instructors cannot simply lecture for an hour and forty minutes (or for three and a half hours in once-a-week classes) and expect their students to stay with them. In addition, they probably cannot expect their students to engage in a full-class discussion for that length of time either.

Group Work:

Since EN-101 and EN-102 are writing and reading classes, there are plenty of opportunities for students to engage singly in both activities during class. However, group work is a way of getting students to collaborate. Also, students who tend to drift into the background in full class discussions and activities have to (or get to) participate when they're only one of four or five. But perhaps most important, group work asks students to meet and know each other, to form a community.

Revision:

As any writing teacher who has been teaching for more than a couple of years will know, revision is one of the most difficult skills to teach. And, as any writer who has been writing for any length of time will attest, it's also one of the most difficult skills to learn (and to learn to enjoy). We sweat blood to create, spend hours staring at a blank screen or piece of paper (or perhaps worse, one full of gibberish) and feel immense relief when we finally have something-anything. We don't want to return to it, we just want to send it on its way-to a teacher, an editor, the wastebasket. Just as the word "revision" suggests, though, for this activity to work, we have tore-see our writing.

These two terms are together in this chapter because our classes at Queensborough are historically large--a 30 cap for 101, a 32 for 102. In classes this big, it is impractical to approach critiques--which can then lead to revision--as full-class workshops. Small groups-anywhere from two to five--are much more wieldy.

Following are some approaches to group work, revision, and critiques used by some

Queensborough English department faculty:

Group Critiques

Peer Editing Eval ! Form

Revision: Hot-spotting

Small Group Work and Inductive Reasoning

Copyright Jodie Childers

"Rather than force them too quickly and exclusively into critical analysis, I'm inclined to think that teachers might do better, first, to meet students where they are, to learn what their literacy aims and aspirations are as we work to help them learn literate discourses valued in the academy."

--R. Mark Hall, "The Oprafication of Literacy, " College English, July 2003.

Asking student to write on the first day of class accomplishes the following goals:

For students who are used to 40-minute high school classes, varying the activities in our hour and forty-minute classes is key to the success of each class session. Some combination of in class writing, small group activities, whole class discussion, a very brief presentation by the teacher, perhaps a media presentation, should provide the structure for each class. [Note that the 4th (conference) hour is absorbed into the class and not necessarily treated separately.]

Below is a suggestion as to how class activities can vary in the pursuit of a single goal:

A more specific variation on this lesson is suggested by David A. Jolliffe of DePaul University (WPA):

Begin the class by doing something that focuses the students' attention on the intellectual substance that will follow in the next 100 minutes. Write a pithy quotation or challenging question on the board and ask students to write for three minutes silently about it. Solve a quick, illustrative problem and pose another one. Plan to use the material you generate later in the session. Do anything except class business.

Let students know your sense of the purpose of the class session--what you hope they will learn--and provide them with an overview of what you and they will be doing during the session.

Take care of any business--announcements, distribution of assignment sheets, and so on. Do anything businesslike here except return graded papers. Do that at the end of the class session, unless you intend to teach about the work they have done in the papers.

Another approach to providing a variety of classroom activities is to scaffold each writing assignment. "Scaffolding gives learners the help they need to move from what they can already do to more complex tasks. Appleby (1984), for example, uses this term to refer to instructional support provided by the teacher but also warns that scaffolding need not be viewed reductively as simply a teacher-centered lesson. Scaffolding also refers to how tasks can be structured and modeled and how the environment for working can be redesigned to support development. Scaffolding is the assistance that proficient members of a community offer to learners. . ." (Carol 91).

In scaffolding, then, the faculty member analyzes each writing assignment and breaks the task into component parts and, then, around each part designs a lesson that engages the students in responding to the task. Often, community college students also need the faculty member to ask them what they already know before deciding where to start the scaffolding process. An ongoing literacy narrative or journal can be helpful to both student and instructor if students write each class period about what they indeed know and don't know about the task.

The QCC English Department has made it a policy not to assign a "blockbuster" research project due at the end of the semester but rather distribute research throughout all assignments over the semester. The reason for this policy is that the blockbuster end-of semester assignment can lead to frustration and result in students' committing plagiarism or dropping the course.

The first three assignments may utilize primary research. For example, the literacy narrative may be revised to include research based on family interviews. Two additional assignments may also be personal writing, such as a memoir or a family history; and an ethnographic study of one's neighborhood. These assignments may engage students in surveys, observations, or reading family letters and other family documents.

By the middle of the semester, students can be introduced to library and web-based research and the apparatus that a handbook will explain to them. Learning research techniques also requires scaffolding from the instructor.

Here is further advice on the pedagogy of teaching the research component:

Patchwriting: When following the language of a source text, students are expected to u. se fresh words and fresh sentence structures. Inadequate paraphrase customarily results in a lower grade for the paper and may also result in a required ungraded revision.

In the following article from the Penn State University Composition Program Handbook, Margaret Lyday describes some general guidelines she has developed that facilitate productive and dynamic class discussions.

Discussion is one of the primary ways to move students from passive to active learners. While passive learners focus primarily on information recall, active learners are able to apply concepts to different contexts and to analyze and evaluate new results.

STRATEGIES FOR COURSE MANAGEMENT

Most students learn successful discussion patterns early in the course. A teacher, like a coach or a director, must be willing to wait, sometimes as long as a minute, for the first brave student to venture a response. Most students are all too happy to let the teacher take over the discussion, and we should simply refuse to supply the pat answer. Sometimes, providing questions for students to write about before class or during the first few minutes of class gives them a head start. Another strategy that is particularly helpful at the beginning of the semester is to group students in twos or threes to share their individual answers and then have someone give the group report. Listing important ideas from each group and then asking for examples or exceptions often will prompt individuals to ask questions of other students and elaborate on their own experiences.

Students need to learn that seldom does one answer or model fit every situation and that a successful writer in any environment is one who can present and support a point in a way that engages and excites the audience. Discussions, then, can develop active learning and critical thinking skills, skills we all need in order to write successfully in ever-changing life situations.

MAKING EFFECTIVE USE OF THE TEACHER/STUDENT CONFERENCE

Excerpts from

"Teaching the Other Self: The Writer's First Reader"

By Donald M. Murray

The act of writing is inseparable from the act of reading. You can read without writing, but you can't write without reading. The reading skill required, however, to decode someone else's finished text may be quite different from the reading skills required to chase a wisp of thinking until it grows into a completed thought.

To follow thinking that has not yet become thought, the writer's other self has to be an explorer, a map-maker. The other self scans the entire territory; forgetting, for the moment, questions of order or language. The writer / explorer looks for the draft's horizons. Once the writer has scanned the larger vision of the territory; it may be possible for him (or her) to trace a trail that will get the writer from here to there, from meaning identified to meaning clarified. Questions of order are now addressed, but questions of language still delayed. Finally, the writer / explorer studies the map in detail to spot the hazards that lie along the trail, the hidden swamps of syntax, the underbrush of verbiage, the voice found, lost, found again. . .

I think we can predict some of the functions that are performed by the other self during the writing process:

This retroactive understanding of what was done makes it possible for the teacher not only to teach the other self but to recruit the other self to assist in the teaching of writing. The teacher brings the other self into existence, and then works with that other self so that, after the student has graduated, the other self can take over the function of the teacher.

When the student speaks and the student and the teacher listen, they are both informed about the nature of the writing process that produced the draft. This is the point at which the teacher knows what needs to be taught or reinforced, one step at a time, and the point at which the student knows what needs to be done in the next draft.

Listening is not a normal composition teacher's skill. We tell and they listen. But to make effective use of the other self the teacher and the student must listen together.

This is done most efficiently in conference. But before the conference, at the beginning of the course, the teacher must explain to the class exactly why the student is to speak first. I tell my students that I'm going to do as little as possible to interfere with their learning. It is their job to read the text, to evaluate it, to decide how it can be improved so that they will be able to write when I am not there. I point out that the ways in which they write are different, their problems and solutions are different, and that I am a resource to help them find their own way. I will always attempt to underteach so that they can overlearn.

I may read the paper before the conference or during the conference, but the student will always speak first in the conference. I have developed a repertoire of questions - what surprised you? what's working best? what are you going to do next? -but I rarely use them. The writing conference is not a social occasion. The student comes to get my response to the work and I give my response to the student's response. I am teaching the other self. . .

The students will discover, as the teacher models an ideal other self, that the largest questions of content, meaning, or focus have to be dealt with first. Until there is a clear meaning the writer cannot order the information that supports that meaning or leads towards it. And until the meaning and its supporting structure are clear, the writer cannot make the decisions about the voice and language that clarify and communicate that meaning. The other self has to monitor many activities and make sure what the writing self reads that is being monitored in an effective sequence.

Sometimes teachers who are introduced to teaching the other self feel that listening to the student first means that they cannot intervene. That is not true. This is not a do-your-own thing kind of teaching. It is a demanding teaching; it is nothing less than the teaching of critical thinking.

Listening is, after all, an aggressive act. When the teacher insists that the student knows the subject and the writing process that produced the draft better than the teacher, and then has faith that the student has another self that has monitored the producing of the draft, then the teacher puts enormous pressure on the student. Intelligent comments are expected, and when they are expected they are often received. . .

The most effective learning takes place when the other self articulates the writing that went well. Too much instruction is failure-centered. It focuses on error and unintentionally reinforces error.

Again and again the teacher listens to what the student is saying - and not saying - to help the student hear that other self that has been monitoring what isn't yet on the page or what may be beginning to appear on the page.

This dialogue between the student's other self and the teacher occurs best in conference. But the conferences should be short and frequent. . .

Copyright Jodie Childers

English Department

Tanya Zhelezcheva

Queensborough Community College provides the opportunity for exceptional students to be challenged by enrolling in an Honors class or by completing an Honors Contract, an independent study within a course. The English Department has been offering Honors Contracts.

Students are eligible for an Honors Contract if they have at least 9 QCC credits with a minimum grade point average (GPA) of 3. 00. Students who do not meet the above requirements, but have demonstrated exceptional abilities in the subject matter may also complete an Honors Contract if they are recommended by faculty. In an EN 101course, where most students have recently enrolled in QCC and have not completed 9 credit hours, the faculty may invite the student to complete an Honors Contract provided the student demonstrates outstanding abilities.

If a student signs an Honors Contract for a select class and completes it, he or she will receive an honors credit for the course which will be designated as a footnote in the transcript. Completing 12 honors credits and obtaining at least a 3. 40 GPA at the time of graduation allows the student to graduate with an Honors Certificate.

If a student signs but does not complete the requirements of the Honors Contract, the student may still finish the class and may receive an A for the course. The faculty are not obliged to sign a contract even though a student may request it.

If a student expresses an interest in working on a challenging project, the faculty needs to submit an Honors Contract (see Attachment B below). Except for the top portion of the Honors Contract, the remainder has to be filled out by the faculty. The document may be compiled after the student and the faculty have discussed their interests or the faculty may design the project without the input of the student.

Previous Honors Contracts from the English Department tend to include a substantial research component, a project or projects that demonstrate sophisticated thinking about a topic, and several meetings (one or two at the discretion of the faculty) between faculty and student to discuss the development of the student's ideas. These requirements also usually lead to lengthier final projects.

The Honors Contracts, which are approved by the Honors Committee, need to stress two key points:

The Honors Contract also requires a visit to the library by a specific date, usually early in the semester. Failure to attend the library session disqualifies the student from obtaining an Honors designation for the class. Students who have already attended the honors library workshop during previous semesters are exempt from this requirement. Some classes visit the library for a library session, but such sessions are different from the library honors workshops, and they are not counted as a requirement for the honors students.

While the Honors Program does not allow incomplete grades, a student may complete the honors contract and still receive a B or lower grade for the course.

Honors students are encouraged to attend the Annual Honors Conference which is usually organized at the end of the Spring semester. While presenting at the conference is not a requirement to receive an honors credit, if a student is interested in delivering a paper at the conference, he or she would need to submit an abstract by a specified deadline. The deadline is usually announced in a campus-wide email with several reminders.

Please note that the deadlines for the submission of the Honors Contract and the Honors Conference are strict.

Here are several important and rough deadlines for faculty to observe:

Week 1: Formulate the requirements for the Honors Contract and specify the date by which the student should submit the final honors project(s).

End of Week 2: Sign the contract and gather signatures from the student and from the chair of the English Department.

Week 3: Submit the Honors Contract(s) to Ms. Carol Imandt at A-503.