A Brief Glimpse into the Immune System

We are surrounded by billions of bacteria and viruses. To many of them, a human being is like a walking smorgasbord, offering nearly limitless resources that they can use for energy and reproduction. Luckily for us, getting into the human body is not an easy task!

We are surrounded by billions of bacteria and viruses. To many of them, a human being is like a walking smorgasbord, offering nearly limitless resources that they can use for energy and reproduction. Luckily for us, getting into the human body is not an easy task!

From the point of view of these tiny organisms, a human is a bit like a fortress. The skin is thick and very hard to penetrate. In addition, the skin also produces a variety of substances that are harmful to invaders. Openings such as the eyes, nose, and mouth are protected by fluids or sticky mucus that capture harmful attackers. The respiratory tract also has mechanical defenses in the form of cilia, tiny hairs that remove particles. Intruders that get as far as the stomach are up against a sea of stomach acid that kills most of them.

But in spite of our fantastic defenses, hostile invaders still manage to get through. Some enter along with our food, while others may sneak in via the nose. And, as we all know, many things can break through our skin. In everyday life we often receive cuts or scrapes, and every time this happens we face the risk of a full-scale invasion from bacteria or viruses. What is the magic, then, that keeps us healthy most of the time?

But in spite of our fantastic defenses, hostile invaders still manage to get through. Some enter along with our food, while others may sneak in via the nose. And, as we all know, many things can break through our skin. In everyday life we often receive cuts or scrapes, and every time this happens we face the risk of a full-scale invasion from bacteria or viruses. What is the magic, then, that keeps us healthy most of the time?

When we receive a cut, and when invaders enter the body, cells are destroyed. The dying cells trigger an automatic response called inflammation, which includes dilated blood vessels and increased blood flow. An inflammation is the body's equivalent to a burglar alarm. Once it goes off, it draws defensive cells to the damaged area in great numbers. Increased blood flow helps defensive cells reach the place where they're needed. It also accounts for the redness and swelling that occur.

Introduction to How the Immune System Works

Introduction to How the Immune System Works

Immune Cells: The Defense

The defensive cells are more commonly known as immunecells. They are part of a highly effective defense force called the immune system. The cells of the immune system work together with different proteins to seek out and destroy anything foreign or dangerous that enters our body. It takes some time for the immune cells to be activated - but once they're operating at full strength, there are very few hostile organisms that stand a chance.

Immune cells are white blood cells produced in huge quantities in the bone marrow. There are a wide variety of immune cells, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Some seek out and devour invading organisms, while others destroy infected or mutated body cells. Yet another type has the ability to release special proteins called antibodies that mark intruders for destruction by other cells.

But the really cool thing about the immune system is that it has the ability to "remember" enemies that it has fought in the past. If the immune system detects a "registered" invader, it will strike much more quickly and more fiercely against it. As a result, an invader that tries to attack the body a second time will most likely be wiped out before there are any symptoms of disease. When this happens, we say that the body has become immune.

But the really cool thing about the immune system is that it has the ability to "remember" enemies that it has fought in the past. If the immune system detects a "registered" invader, it will strike much more quickly and more fiercely against it. As a result, an invader that tries to attack the body a second time will most likely be wiped out before there are any symptoms of disease. When this happens, we say that the body has become immune.

Bacteria and Viruses: Our Main Enemies

A virus needs a host cell to reproduce

.

Now that you know a bit about our defenses, let's take a closer look at our primary enemies. Bacteria and viruses are the organisms most often responsible for attacking our bodies.

Most bacteria are free living, while others live in or on other organisms, including humans. Unfortunately, many bacteria that have human hosts produce toxins (poisons) that damage the body. Not all bacteria are harmful, though. Some are neutral and many are even desirable as they fulfill important functions in the body.

Bacteria are complete organisms that reproduce by cell division. Viruses, on the other hand, cannot reproduce on their own. They need a host cell. They hijack body cells of humans or other species, and trick them into producing new viruses that can then invade other cells. Frequently, the host cell is destroyed during the process.

Pathogens and Antigens

In daily life we might speak of viruses, bacteria, and toxins. However, when reading about the immune system you'll often come across the words antigenand pathogen. An antigen is a foreign substance that triggers a reaction from the immune system. Antigens are often found on the surfaces of bacteria and viruses. A pathogen is a microscopic organism that causes sickness. Hostile bacteria and viruses are examples of pathogens.

Reference:

"The Immune System - Overview". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 19 Jul 2015. <http://www.nobelprize.org/educational/medicine/immunity/immune-overview.html>

The Immune System - in More Detail

The immune system is one of nature's more fascinating inventions. With ease, it protects us against billions of bacteria, viruses, and other parasites. Most of us never reflect upon the fact that while we hang out with our friends, watch TV, or go to school, inside our bodies, our immune system is constantly on the alert, attacking at the first sign of an invasion by harmful organisms.

The immune system is one of nature's more fascinating inventions. With ease, it protects us against billions of bacteria, viruses, and other parasites. Most of us never reflect upon the fact that while we hang out with our friends, watch TV, or go to school, inside our bodies, our immune system is constantly on the alert, attacking at the first sign of an invasion by harmful organisms.

The immune system is very complex. It's made up of several types of cells and proteins that have different jobs to do in fighting foreign invaders. In this section, we'll take a look at the parts of the immune system in some detail.

The Complement System

The first part of the immune system that meets invaders such as bacteria is a group of proteins called the complement system. These proteins flow freely in the blood and can quickly reach the site of an invasion where they can react directly withantigens - molecules that the body recognizes as foreign substances. When activated, the complement proteins can

- trigger inflammation

- attract eater cells such as macrophages to the area

- coat intruders so that eater cells are more likely to devour them

- kill intruders

Phagocytes

This is a group of immune cells specialized in finding and "eating" bacteria, viruses, and dead or injured body cells. There are three main types, the granulocyte, the macrophage, and the dendritic cell.

The granulocytes often take the first stand during an infection. They attack any invaders in large numbers, and "eat" until they die. The pus in an infected wound consists chiefly of dead granulocytes. A small part of the granulocyte community is specialized in attacking larger parasites such as worms.

The granulocytes often take the first stand during an infection. They attack any invaders in large numbers, and "eat" until they die. The pus in an infected wound consists chiefly of dead granulocytes. A small part of the granulocyte community is specialized in attacking larger parasites such as worms.

The macrophages ("big eaters") are slower to respond to invaders than the granulocytes, but they are larger, live longer, and have far greater capacities. Macrophages also play a key part in alerting the rest of the immune system of invaders. Macrophages start out as white blood cells called monocytes. Monocytes that leave the blood stream turn into macrophages.

The macrophages ("big eaters") are slower to respond to invaders than the granulocytes, but they are larger, live longer, and have far greater capacities. Macrophages also play a key part in alerting the rest of the immune system of invaders. Macrophages start out as white blood cells called monocytes. Monocytes that leave the blood stream turn into macrophages.

The dendritic cells are "eater" cells and devour intruders, like the granulocytes and the macrophages. And like the macrophages, the dendritic cells help with the activation of the rest of the immune system. They are also capable of filtering body fluids to clear them of foreign organisms and particles.

The dendritic cells are "eater" cells and devour intruders, like the granulocytes and the macrophages. And like the macrophages, the dendritic cells help with the activation of the rest of the immune system. They are also capable of filtering body fluids to clear them of foreign organisms and particles.

Lymphocytes - T cells and B cells

The lymphatic system

The receptors match only one specific antigen

White blood cells called lymphocytes originate in the bone marrow but migrate to parts of the lymphatic system such as the lymph nodes, spleen, and thymus. There are two main types of lymphatic cells, T cells and B cells. The lymphatic system also involves a transportation system - lymph vessels - for transportation and storage of lymphocyte cells within the body. The lymphatic system feeds cells into the body and filters out dead cells and invading organisms such as bacteria.

On the surface of each lymphatic cell are receptors that enable them to recognize foreign substances. These receptors are very specialized - each can match only one specific antigen.

To understand the receptors, think of a hand that can only grab one specific item. Imagine that your hands could only pick up apples. You would be a true apple-picking champion - but you wouldn't be able to pick up anything else.

In your body, each single receptor equals a hand in search of its "apple." The lymphocyte cells travel through your body until they find an antigen of the right size and shape to match their specific receptors. It might seem limiting that the receptors of each lymphocyte cell can only match one specific type of antigen, but the body makes up for this by producing so many different lymphocyte cells that the immune system can recognize nearly all invaders.

T Cells

T cells come in two different types, helper cells and killer cells. They are named T cells after the thymus, an organ situated under the breastbone. T cells are produced in the bone marrow and later move to the thymus where they mature.

Helper T cells are the major driving force and the main regulators of the immune defense. Their primary task is to activate B cells and killer T cells. However, the helper T cells themselves must be activated. This happens when a macrophage or dendritic cell, which has eaten an invader, travels to the nearest lymph node to present information about the captured pathogen. The phagocyte displays an antigen fragment from the invader on its own surface, a process called antigen presentation. When the receptor of a helper T cell recognizes the antigen, the T cell is activated. Once activated, helper T cells start to divide and to produce proteins that activate B and T cells as well as other immune cells.

Helper T cells are the major driving force and the main regulators of the immune defense. Their primary task is to activate B cells and killer T cells. However, the helper T cells themselves must be activated. This happens when a macrophage or dendritic cell, which has eaten an invader, travels to the nearest lymph node to present information about the captured pathogen. The phagocyte displays an antigen fragment from the invader on its own surface, a process called antigen presentation. When the receptor of a helper T cell recognizes the antigen, the T cell is activated. Once activated, helper T cells start to divide and to produce proteins that activate B and T cells as well as other immune cells.

The killer T cell is specialized in attacking cells of the body infected by viruses and sometimes also by bacteria. It can also attack cancer cells. The killer T cell has receptors that are used to search each cell that it meets. If a cell is infected, it is swiftly killed. Infected cells are recognized because tiny traces of the intruder, antigen, can be found on their surface.

B Cells

The B lymphocyte cell searches for antigen matching its receptors. If it finds such antigen it connects to it, and inside the B cell a triggering signal is set off. The B cell now needs proteins produced by helper T cells to become fully activated. When this happens, the B cell starts to divide to produce clones of itself. During this process, two new cell types are created, plasma cells and B memory cells.

The plasma cell is specialized in producing a specific protein, called an antibody that will respond to the same antigen that matched the B cell receptor. Antibodies are released from the plasma cell so that they can seek out intruders and help destroy them. Plasma cells produce antibodies at an amazing rate and can release tens of thousands of antibodies per second.

When the Y-shaped antibody finds a matching antigen, it attaches to it. The attached antibodies serve as an appetizing coating for eater cells such as the macrophage. Antibodies also neutralize toxins and incapacitate viruses, preventing them from infecting new cells. Each branch of the Y-shaped antibody can bind to a different antigen, so while one branch binds to an antigen on one cell, the other branch could bind to another cell - in this way pathogens are gathered into larger groups that are easier for phagocyte cells to devour. Bacteria and other pathogens covered with antibodies are also more likely to be attacked by the proteins from the complement system.

The Memory Cells are the second cell type produced by the division of B cells. These cells have a prolonged life span and can thereby "remember" specific intruders. T cells can also produce memory cells with an even longer life span than B memory cells. The second time an intruder tries to invade the body, B and T memory cells help the immune system to activate much faster. The invaders are wiped out before the infected human feels any symptoms. The body has achieved immunity against the invader.

References - "The Immune System - in More Detail". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 19 Jul 2015. <http://www.nobelprize.org/educational/medicine/immunity/immune-detail.html>

https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=112&v=Non4MkYQpYA

Introduction to how the Immune System works.

http://reneepoon.tripod.com/id14.html

HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS

A Worldwide Epidemic

AIDS was first reported in the United States in 1981 and has since become a major worldwide epidemic. It is the most catastrophic disease in modern history. It has become the world's deadliest infectious disease and is threatening to eliminate up to a sixth of the world's population. AIDS is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV. By killing or damaging cells of the body's immune system, HIV progressively destroys the body's ability to fight infections and certain cancers. People diagnosed with AIDS may get life-threatening diseases called opportunistic infections. These infections are caused by microbes such as viruses or bacteria that usually do not make healthy people sick.

Scientists identified a type of chimpanzee in West Africa as the source of HIV infection in humans. They believe that the chimpanzee version of the immunodeficiency virus (called simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV) most likely was transmitted to humans and mutated into HIV when humans hunted these chimpanzees for meat and came into contact with their infected blood. Studies show that HIV may have jumped from apes to humans as far back as the late 1800s. Over decades, the virus slowly spread across Africa and later into other parts of the world. We know that the virus has existed in the United States since at least the mid- to late 1970s.

Scientists identified a type of chimpanzee in West Africa as the source of HIV infection in humans. They believe that the chimpanzee version of the immunodeficiency virus (called simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV) most likely was transmitted to humans and mutated into HIV when humans hunted these chimpanzees for meat and came into contact with their infected blood. Studies show that HIV may have jumped from apes to humans as far back as the late 1800s. Over decades, the virus slowly spread across Africa and later into other parts of the world. We know that the virus has existed in the United States since at least the mid- to late 1970s.

Video- Documentary 1987 "Patient Zero"

Video- Documentary 1987 "Patient Zero"

HIV Prevalence/Incidence Estimate

Since 1981, more than 980,000 cases of AIDS have been reported in the United States to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). According to the CDC, more than 1,000,000 Americans may be infected with HIV, one-quarter of whom are unaware of their infection. An estimated 33.3 million people worldwide are infected with HIV. More than 2 million people die from it each year. 2.6 million people were newly infected in 2009 according to the World Health Organization/UNAIDS. In 2009 there were approximately 1.8 million deaths from AIDS. Most people with HIV live in developing countries. The epidemic is growing most rapidly among minority populations and is a leading killer of African-American males ages 25 to 44. According to the CDC, AIDS affects nearly seven times more African Americans and three times more Hispanics than whites. In recent years, an increasing number of African-American women and children are being affected by HIV/AIDS. (National Institute of Health)

New treatments are helping people with HIV live longer. But about a quarter of all people with HIV do not know that they have it. About 550,000 people die from HIV-related conditions each year in the United States.

The number of people living with AIDS is increasing, as effective new drug therapies keep HIV-infected persons healthy longer and dramatically reduce the death rate. The Centers for Disease Control's (CDC) programs work to improve treatment, care and support for persons living with HIV/AIDS and to build capacity and infrastructure to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States and around the world. From 2006 to 2009 the estimated number of people living with HIV increased 8.2%.

In 2010 our nation's primary concern was to control and end the HIV epidemic in 2011. President Obama initiated major policy shifts affecting HIV prevention.

CDC Fact Sheets -

Cuomo Plan Seeks to End New York's AIDS Epidemic -

Video - Understanding the virus

Video - Understanding the virus

Let's Meet the HIV Virus

HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus. It is the virus that can lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS. Unlike some other viruses, the human body cannot get rid of HIV. That means that once you have HIV, you have it for life.

No safe and effective cure currently exists, but scientists are working hard to find one, and remain hopeful. Meanwhile, with proper medical care, HIV can be controlled. Treatment for HIV is often called antiretroviral therapy or ART. It can dramatically prolong the lives of many people infected with HIV and lower their chance of infecting others. Before the introduction of ART in the mid-1990s, people with HIV could progress to AIDS in just a few years. Today, someone diagnosed with HIV and treated before the disease is far advanced can have a nearly normal life expectancy.

HIV affects specific cells of the immune system, called CD4 cells, or T cells. Over time, HIV can destroy so many of these cells that the body can't fight off infections and disease. When this happens, HIV infection leads to AIDS.

Video - HIV Replication in the Cell

Video - HIV Replication in the Cell

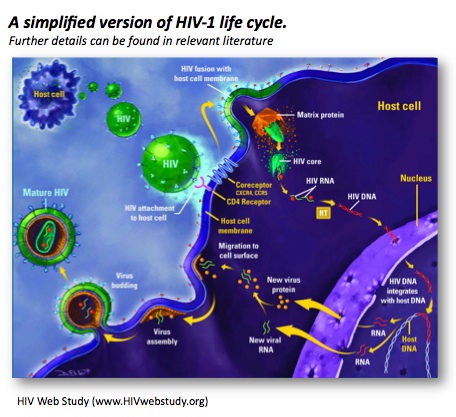

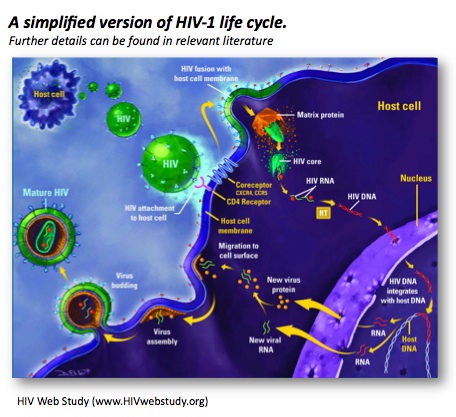

HIV is classified as a retrovirus that has a long latency period. HIV invades the body through the bloodstream and uses the immune system against itself. As the macrophages recognize the invader, they attack just as they would for any other foreign substance.HIV virus is passed from one person to another through blood and body fluids. It then travels through the bloodstream to many different places in the body. Some of the HIV are destroyed when the helper T cells join the battle, however, the HIV attach themselves to the T cells and the T cells accept the foreign cells as their own. The outer covering of the two cells fuse. This defense is coordinated by the helper T cells. But the HIV virus has a unique battle strategy; it attacks the T cells themselves, crippling the body's defenses. HIV has a special shape on its surface which, like a piece of a jigsaw puzzle, fits perfectly into a shape on the T cell. This shape is a protein called CD4. HIV uses CD4 to enter the cells it infects. This is why the T helper cell is referred to as a CD4 lymphocyte.

Once inside the T-4 cell, HIV uses a reverse transcriptase enzyme to translate its own genetic program ribonucleic acid (RNA) into the T-4 cells' genetic material deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Instead of fighting against the infection, the T cell is programmed to either produce more HIV cells or to remain dormant. Once inside a T helper cell, HIV takes over the cell and the virus then replicates. The virus's genetic information (RNA) is transcribed into a form that is identical to the cell's genetic information (DNA). The virus, now in the form of DNA, hides out inside the nucleus of the cell, escaping from the body's defenses. After a while, HIV comes out of hiding and begins to reproduce. The proteins are cut into usable pieces and packaged with the RNA. The new viruses then bud from the cell. Each new virus may then go on to infect and destroy other T cells, weakening the immune system's defense.

HIV Transmission

Video - HIV/AIDS 101 (CDC)

Video - HIV/AIDS 101 (CDC)

The blood, semen, vaginal fluid, and breast milk of people infected with HIV has enough of the virus in it to infect other people. It has not been documented as fact that HIV can be transmitted through tears and saliva, but CDC has kept saliva on the list of body fluids that require the healthcare professional to exercise standard precautions. CDC and the American Dental Association's Council on Dental Therapeutics suggest assuming that saliva containing a lot of blood could potentially carry HIV and other harmful pathogens.

An HIV infected person who has no signs of an infection or illness can still infect others.

There are four known common ways HIV is transmitted:

1. Sexual intercourse,

2. Sharing of needles and syringes,

3.Body fluids (blood, semen, vaginal fluid, and breast milk, and

4. Babies born of infected mothers and drinking breast mile of infected mot

HIV can enter the body through certain types of tissues that line the anus, vagina, or penis. It also can enter through cuts or tears in the vagina, rectum, penis, or mouth. HIV can be spread through unprotected sexual intercourse from male-to-male, male-to-female, or female-to-female. Unprotected sexual intercourse means sexual intercourse without correct and consistent use of a latex condom or any other physical barrier to HIV. It is possible to catch HIV through oral sex if there are open sores in a person's mouth or bleeding gums.

Insects such as mosquitoes, bugs or animals do not spread HIV. HIV is also not spread through casual contact of any kind such as:

1. Sharing a telephone

2.Toilet seats/ doorknobs

3. Sharing dishes

4. Holding hands, hugging, etc.

-

HIV Infection Cycle

HIV disease has a well-documented progression. Untreated, HIV is almost universally fatal because it eventually overwhelms the immune system—resulting in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). HIV treatment helps people at all stages of the disease, and treatment can slow or prevent progression from one stage to the next.

A person can transmit HIV to others during any of these stages:

Window Period -Acute infection: Within 2 to 4 weeks after infection with HIV, a person may feel sick with flu-like symptoms. The time period after contracting the infection and until the body has developed enough antibodies for an accurate positive test result. This is called acute retroviral syndrome (ARS) or primary HIV infection, and it's the body's natural response to the HIV infection. (Not everyone develops ARS, however—and some people may have no symptoms.)

During this period of infection, large amounts of HIV are being produced in the body. The virus uses important immune system cells called CD4 cells to make copies of itself and destroys these cells in the process. Because of this, the CD4 count can fall quickly.

The ability to spread HIV is highest during this stage because the amount of virus in the blood is very high.

Eventually, the immune response will begin to bring the amount of virus in the body back down to a stable level. At this point, the CD4 count will then begin to increase, but it may not return to pre-infection levels.

Clinical latency (inactivity or dormancy): This period is sometimes called asymptomatic HIV infection or chronic HIV infection. During this phase, HIV is still active, but reproduces at very low levels. You may not have any symptoms or get sick during this time. People who are on antiretroviral therapy (ART) may live with clinical latency for several decades. For people who are not on ART, this period can last up to a decade, but some may progress through this phase faster. It is important to remember that you are still able to transmit HIV to others during this phase even if you are treated with ART, although ART greatly reduces the risk. Toward the middle and end of this period, your viral load begins to rise and your CD4 cell count begins to drop. As this happens, you may begin to have symptoms of HIV infection as your immune system becomes too weak to protect you.

AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome): This is the stage of infection that occurs when your immune system is badly damaged and you become vulnerable to infections and infection-related cancers called opportunistic illnesses. When the number of your CD4 cells falls below 200 cells per cubic millimeter of blood (200 cells/mm3), you are considered to have progressed to AIDS. (Normal CD4 counts are between 500 and 1,600 cells/mm3.) You can also be diagnosed with AIDS if you develop one or more opportunistic illnesses, regardless of your CD4 count. Without treatment, people who are diagnosed with AIDS typically survive about 3 years. Once someone has a dangerous opportunistic illness, life expectancy without treatment falls to about 1 year. People with AIDS need medical treatment to prevent death.

Video -HIV Symptoms and Signs

Video -HIV Symptoms and Signs

Women Living with HIV

Women represent the fastest growing population of HIV/AIDS groups in the U.S. Women are diagnosed later than men because of the route of transmission, clinical manifestations, survival time, impact on reproductive health such as child bearing, gynecological disease and social factors.

Today, women make up nearly half of all the AIDS cases worldwide. In the last twenty years, the proportion of U.S. AIDS cases in women has more than tripled from 8% in 1985 to 27% in 2004 (CDC).

AIDS is the sixth leading cause of death in women 25 to 34 years of age in the U.S. and is the leading cause of death in African women in the same age group.

Most of the AIDS cases in adolescents are young women who are of African and Latin American decent. They are more likely to be infected through heterosexual intercourse.

Due to the prolonged incubation period from HIV infection to the time of an AIDS diagnosis it is probable that infection occurred during adolescents (CDC). Recent studies have shown that women with AIDS survive a shorter time than men when they are diagnosed later in the disease process. This may be due to poorer access to or use of the healthcare resources, homelessness, domestic violence, and lack of community support.

The most common cause of death in women was due to PCP, bacterial pneumonia, and toxoplasmosis. Women also demonstrated a higher incidence of candida infections, chronic or recurrent mucosocutaneous herpes and simplex infections. Men had a higher incidence of PCP and Kaposi's sarcoma.

HIV-positive women who are thinking about getting pregnant -- or already are pregnant -- have options that can help them stay healthy and protect their babies from becoming HIV-infected.

Since the mid-1990s, HIV testing and preventive measures have resulted in more than a 90% decline in the number of children in the U.S. infected with HIV in the womb. And after three decades of research, doctors now understand how to craft a detailed plan to keep babies of HIV-positive women from getting the virus.

One way of decreasing HIV in the newborn is to have the baby and mother tested prior to delivery. Naturally, the mother has to consent and the procedure must be explained to the mother at her level of understanding. If there is a chance that the baby will get HIV experts are now recommending several medications to reduce the newborn's chances of acquiring HIV. One is AZT and is given through the mother's vein. The other is a pill called Nevirapine. After the baby is born the doctor may place the newborn on AZT syrup. These medicines have been studied for use in pregnant women and newborns, and there have been no serious side effects.

Medications Are Key

HIV is passed from one person to another through blood, semen, genital fluids, and breast milk. Pregnancy, labor and delivery, and breastfeeding all pose a risk of passing HIV along to the baby.

Multiple studies have found that prevention starts with antiretroviral drugs. These medications were first approved in the 1990s, and researchers soon learned that combining three of them -- called an antiretroviral (ART) regimen -- added up to a lot of protection for a baby in the womb.

Starting women on well-tolerated antiretroviral medications as early as possible, can reduce the risk of transmission to less than 2%.

The drugs lower the amount of virus in the body, which lowers the risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Some anti-HIV medications also pass from the pregnant mother to her baby through the placenta. This helps protect the baby from HIV.

No Missed Doses

For all of this to work, the mom must commit to taking her ART regimen, which can sometimes be a challenge during pregnancy.

The key to keeping the virus suppressed in both the mother and baby is to make sure that she is taking her medications every day.

Preventive Meds for Baby – No Breastfeeding

During labor and delivery, when the baby may be exposed to HIV in the mother's genital fluids or blood, pregnant women infected with HIV get a steady intravenous drip of the antiretroviral drug AZT, while continuing to take their usual drugs by mouth.

Once they're born, babies get liquid AZT in a syrup for 6 weeks as a preventive measure. The babies whose moms didn't take anti-HIV meds during pregnancy may be given other anti-HIV medications along with AZT.

The final part of the care plan is to avoid breastfeeding, since breast milk is one of the primary body fluids through which HIV is passed.

The combination of viral suppression, not breastfeeding, and giving the baby liquid ART after birth are the keys to having an HIV-negative baby,

Mothers are encouraged to wait until the results of the confirmatory test are given before starting breastfeeding. The tragedy of HIV is that few women are aware of the risk and are not aware of their illness until their child becomes ill. The CDC has advocated universal counseling and testing for every pregnant woman regardless of geography, identified risk behavior, or self-identified risk. The pregnant patient may decline these services and the healthcare provider must document this has occurred.

Healthcare Workers

The main cause of infection in healthcare work settings is exposure to HIV-infected blood via a percutaneous injury (i.e. from needles, instruments, bites which break the skin, etc.

The average risk for HIV transmission after such exposure to infected blood is low; about 3 per 1,000 injuries (CDC, 2007). Certain specific factors may mean a percutaneous injury carries a higher risk, for example:

• A deep injury

• Late-stage HIV disease in the source patient

• Visible blood on the device that caused the injury

• Injury with a needle that had been placed in a source patient's artery or vein.

If percutaneous exposure occurs then the site of exposure should be washed liberally with soap and water but, without scrubbing. Bleeding should be encouraged by pressing gently around the site of the injury. It is important not to press immediately on the injury site and to cleanse wound under running water. Although infection through needle-stick injury does not often occur, it can be devastating for the person.

HIV has been acquired through contact with non-intact skin or mucous membranes (i.e. splashes of infected blood in the eye) in a small number of situations. Research suggests that the risk of HIV infection after mucous membrane exposure is less than 1 in 1000. If mucocutaneous exposure occurs then the affected area should be washed thoroughly with soap and water. If the eye is affected, it should be irrigated thoroughly.

If intact skin is exposed to HIV infected blood then there is no risk of HIV transmission.

TREATMENT AFTER EXPOSURE TO HIV

WHAT IS POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS?

Prophylaxis means disease prevention. Post-exposure prophylaxis (or PEP) means taking antiretroviral medications (ARVs) as soon as possible after exposure to HIV, so that the exposure will not result in HIV infection. These medications are only available with a prescription. PEP should begin within as soon as possible after exposure to HIV but certainly within 72 hours. Treatment with 2 or 3 ARVs should continue for 4 weeks, if tolerated.

WHO SHOULD USE PEP?

Workplace exposure

PEP has been standard procedure since 1996 for healthcare workers exposed to HIV. Workers start taking medications within a few hours of exposure. Usually the exposure is from a "needle stick," when a health care worker accidentally gets jabbed with a needle containing HIV-infected blood. PEP reduced the rate of HIV infection from workplace exposures by 79%. However, some health care workers who take PEP still get HIV infection.

HOW IS PEP TAKEN?

PEP should be started as soon as possible after exposure to HIV. The medications used in PEP depend on the exposure to HIV. The following situations are considered serious exposure:

• Exposure to a large amount of blood.

• Blood came in contact with cuts or open sores on the skin.

• Blood was visible on a needle that stuck someone.

• Exposure to blood from someone who has a high viral load (a large amount of virus in the blood).

For serious exposures, the U.S. Public Health Service recommends using a combination of three approved ARVs for four weeks. For less serious exposure, the guidelines recommend four weeks of treatment with two drugs: AZT and 3TC.

WHAT ARE THE SIDE EFFECTS?

The most common side effects from PEP medications are nausea and generally not feeling well. Other possible side effects include headaches, fatigue, vomiting and diarrhea.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is the use of ARVs as soon as possible after exposure to HIV, to prevent HIV infection. PEP can reduce the rate of infection in health care workers exposed to HIV by 79%.

PEP is a four-week program of two or three ARVs, several times a day. The medications have serious side effects that can make it difficult to finish the program. PEP is not 100% effective; it cannot guarantee that exposure to HIV will not become a case of HIV infection.

CDC guidelines on PEP are on the Internet. Occupational exposure: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5409a1.htm

Source: The AIDS Infonet

Screen Testing

The only way to know if someone is infected with HIV is to be tested. A person cannot rely only on symptoms to know whether they have HIV. Many people who are infected with HIV do not have any symptoms at all for 10 years or more. Some people who are infected with HIV report having flu-like symptoms (often described as "the worst flu ever") 2 to 4 weeks after exposure. Symptoms can include:

• Fever

• Enlarged lymph nodes

• Sore throat

• Rash

These symptoms can last anywhere from a few days to several weeks. During this time, HIV infection may not show up on an HIV test, but people who have it are highly infectious and can spread the infection to others.

However, one should not assume they have HIV if they have any of these symptoms. Each of these symptoms can be caused by other illnesses. Again, the only way to determine whether one is infected is to be tested for HIV infection.

Resources on where to find a testing site:

• Visit National HIV and STD Testing Resources and enter your ZIP code.

• Text your ZIP code to KNOWIT (566948), and you will receive a text back with a testing site near you.

• Call 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636) to ask for free testing sites in your area.

These resources are confidential. A health care provider can also administer an HIV test.

Types of Tests

ELISA stands for enzyme-linked immuno assay. It is a commonly used laboratory test to detect HIV antibodies in the blood. A blood sample is drawn, sent to a lab and the results are available within several days to several weeks.

A negative screening test means a person is not infected with HIV, and does not require further testing. If a person has risky behaviors they could be in the window period and a repeat test is suggested in six months.

A positive screening test means the person needs further testing. A Western Blot, or immunofluorescence assay (IFA), is performed to confirm the diagnosis of HIV.

A rapid test licensed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), known as the Single Use Diagnostic System for HIV-1 (SUDS) can give HIV-1 test results in 5 to 30 minutes. Another rapid test is Ora Quick Rapid HIV Test.

In March 2004, the Ora Quick Rapid HIV Test was approved, by the FDA, for use on Oral Fluid. A reactive HIV test result from either of these tests needs to be confirmed by an additional, more specific test. The patient having a rapid test can be advised immediately of their screening test results, and counseled on HIV prevention and transmission. A negative rapid test result is always negative, unless the patient has been tested before the antibodies have formed (window period).

Two types of home testing kits are available in most drugstores or pharmacies: one involves pricking a finger for a blood sample, sending the sample to a laboratory, then phoning in for results. The other involves getting a swab of fluid from your mouth, using the kit to test it, and reading the results in 20 minutes. Confidential counseling and referrals for treatment are available with both kinds of home tests.

Test Counseling

The person being tested should be informed of the process prior to being tested and it is highly recommended that positive results be given face to face. HIV test subjects should have a counseling session which includes the following topics:

- The meaning of the test results and the possible need for retesting.

- The potential medical, social, and economic effects of a positive test result.

- Availability of healthcare, mental health, social and support services.

- Other appropriate referrals (e.g., STD, psychosocial, primary care).

- Information on reducing the risk of transmission and options for eliminating risks.

- Information on the increased risk for TB and the appropriate place to go for TB testing and treatment.

Video - Mock Rapid HIV testing and Counseling

Video - Mock Rapid HIV testing and Counseling

Complications - Opportunistic Infections (OIs)

People infected with HIV eventually develop symptoms that usually last a long time and are often severe. These symptoms include enlarged lymph glands, fever, tiredness, loss of appetite and weight loss, diarrhea, and night sweats.

As the immune system becomes weaker, the infected person becomes more susceptible to illnesses that normally do not occur in healthy people.

When a person living with HIV gets certain infections (called opportunistic infections, or OIs), he or she will get a diagnosis of AIDS, the most serious stage of HIV infection. AIDS is also diagnosed if a type of blood cell that fights infection (known as CD4 cells) falls below a certain level in persons with HIV. These blood cells are a critical part of a person's immune system.

Opportunistic infections are named that because they take advantage of damage to the immune system and rarely occur in people with a healthy immune system. Healthcare professional must stay current with these guidelines and yearly updates. CDC has developed guidelines in conjunction with U.S. Public Health Service and IDSA for the prevention of opportunistic infections among HIV-infected individuals. The report gives guidelines specific to each type of opportunistic infection.

The most common opportunistic infections are:

• Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP)

• Cytomegalovirus infection (CMV)

• Toxoplasmosis

• Cryptococcus

• Tuberculosis

• Candidiasis

• Kaposis's sarcoma

• Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)

• Cryptosporidium enterocolitis

• HIV dementia

• Malignancies (cancers)

• HIV lipodystrophy

• Chronic wasting from HIV infection

Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP)

PCP is a pneumonia caused by the fungal organism Pneumocystis carinii, which is widespread in the environment, and is not a pathogen (does not cause illness) in healthy individuals.

In clients with AIDS, PCP usually develops slowly and is less severe than for clients with PCP who do not have AIDS. PCP was a relatively rare infection prior to the AIDS epidemic. Before the use of preventive antibiotics for PCP, up to 70% of individuals in the U.S. with advanced AIDS developed PCP.

Symptoms are fever, cough, often mild and dry, shortness of breath, especially with exertion, and rapid breathing.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

CMV is a large herpes-type virus commonly found in humans that can cause serious infections in people with impaired immunity. CMV esophagitis, which may lead to ulcers, is treated with antiviral medications, which may stop the replication of the virus but will not destroy it.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is found in humans worldwide, and in many species of animals and birds. Cats are the definitive host of the parasite.

Human infection results from ingestion of contaminated soil, careless handling of cat litter, ingestion of raw or undercooked meat (lamb, pork, and beef), transmission from a mother to a fetus through the placenta (congenital infection), or by blood transfusion or solid organ transplantation. Over 80-90% of primary infections produce no symptoms. The incubation period for symptoms is 1 to 2 weeks. Symptoms are in immunosuppressed persons:

• Brain lesions associated with fever, headache, confusion, seizures, and abnormal neurological findings.

• Retinal inflammation causing blurred vision.

Cryptococcus

Cryptococcus neoformans is yeast that seldom causes infection in people with normal immune systems. It is one of the more common life-threatening fungal infections in AIDS clients.

Cryptococcus is ordinarily found in soil. Once inhaled, infection with cryptococcosis may heal on its own, remain localized in the lungs, or spread throughout the body (disseminate). Symptoms are:

• Chest pain

• Dry cough

• Headache

• Skin rash or lesion (pinpoint red spots – petechiae)

• Bleeding into the skin

• Bruises

• Unintentional weight loss

• Appetite loss

• Abdominal fullness prematurely after meals

• Abdominal pain

• Weakness

• Numbness and tingling

• Nerve pain or pain along the path of a specific nerve

• Pain along a nerve root (major pathway from the spinal cord)

TB and HIV

People infected with HIV and TB have a 100 times greater risk of developing active TB and becoming infectious compared to those people who are not infected with HIV.

CDC estimates that 10% to 15 % of all TB cases and nearly 30% of cases among people 25 to 44 years of age are occurring in HIV infected individuals. Therefore the following guidelines for the treatment of HIV- related TB have been developed.

Directly observe therapy (DOT) for all patients with HIV-related TB

Improved prognosis with the use of potent antiretroviral therapy

The use of a 6 month regimen consisting of an initial phase of isoniazid, rifabutin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol given for 2 months followed by isoniazid and rifabutin for 4 months. Prolonged treatment up to 9 months for patients with a delayed clinical or bacteriological response to therapy or with cavitary disease on chest radiograph.

Video - AIDS Basics

Video - AIDS Basics

Treatments

Presently there is no cure for HIV. Vaccines are under development but are not yet available.

Medications

There are six major types of drugs used to treat HIV/AIDS. Called antiretrovirals because they act against the retrovirus HIV, these drugs are grouped by how they interfere with steps in HIV replication .

- Entry Inhibitors interfere with the virus' ability to bind to receptors on the outer surface of the cell it tries to enter. When receptor binding fails, HIV cannot infect the cell.

- Fusion Inhibitors interfere with the virus's ability to fuse with a cellular membrane, preventing HIV from entering a cell.

- Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors prevent the HIV enzyme reverse transcriptase (RT) from converting single-stranded HIV RNA into double-stranded HIV DNA―a process called reverse transcription. There are two types of RT inhibitors:

1. Nucleoside/nucleotide RT inhibitors (NRTIs) are faulty DNA building blocks. When one of these faulty building blocks is added to a growing HIV DNA chain, no further correct DNA building blocks can be added on, halting HIV DNA synthesis.

2. Non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs) bind to RT, interfering with its ability to convert HIV RNA into HIV DNA

- Integrase Inhibitors block the HIV enzyme integrase, which the virus uses to integrate its genetic material into the DNA of the cell it has infected.

- Protease Inhibitors interfere with the HIV enzyme called protease, which normally cuts long chains of HIV proteins into smaller individual proteins. When protease does not work properly, new virus particles cannot be assembled.

- Multi-class Combination Products combine HIV drugs from two or more classes, or types, into a single product.

To prevent strains of HIV from becoming resistant to a type of antiretroviral drug, healthcare providers recommend that people infected with HIV take a combination of antiretroviral drugs in an approach called highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Developed by NIAID-supported researchers, HAART combines drugs from at least two different classes.

The success of this therapy is dependent not only on the HAART treatment plan, but also on the patient's ability to strictly adhere to the new medication regimen and tolerate the side effects of these powerful drugs. Side effects that may seem minor, such as fever, nausea, and fatigue, can mean there are serious problems. More serious side effects of HAART are:

- fat maldistribution (lipodystrophy syndrome),

- increased bleeding in patients with hemophilia,

- decreased bone density, and skin rash

Antiretroviral drugs used in the treatment of HIV infection

Medication Chart

Medication Chart

Nutritional Care

One area that is often overlooked is the nutritional state of the person who is HIV/AIDS positive. Nutritional care is a vital, integral, and cost effective way to improve the overall health status of a person who is HIV/AIDS positive.

HIV/AIDS positive person can be empowered to manage the nutritional aspect of self-care. Malnutrition is often associated with HIV/AIDS disease.

Malnutrition develops because the body has a greater need for calories, protein, vitamins and minerals. These increasing nutritional demands can be due to pregnancy or fever. Many people who are suffering from malnutrition have a decreased desire or tolerance for healthy foods due to the following:

- Pain (sore mouth) due to Opportunistic Infections, Thrush, and Poor Dentition.

- Decreased Appetite due to illness, drug related anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and taste changes.

- Neurological Complications due to dysphasia, dementia, and lack of coordination.

- Financial barriers due to homelessness, jobless, and lack of insurance

- Problems with Food Access due to fatigue, disability, lack of social support, and lack of transportation

- Malabsorption due to HIV related changes in the GI tract, HIV drugs with side effects of diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting

The standard of care for the HIV/AIDS person is that nutrition should be guided by a registered dietician.

The Dietician does a baseline nutritional assessment, dietary counseling, on-going assessments, counseling and aggressive interventions as indicated. The dietician also provides diet-drug counseling, like timing of medications versus food intake and symptom management.

The following are brief dietary guidelines that the dietician considers in providing care to the HIV/AIDS client.

- To decrease cholesterol a standard heart healthy diet can be followed. Listed is what is suggested to be generally effective:

<30% of calories from fat

- Possible use of lipid lowering agents, and caution with exercise with very high lipids due to possible infarcts occurring.

To achieve or maintain glycemic control the following has been recommended:

- No concentrated sweets, and

- Consistency in amount and timing of carbohydrates.

To lower triglycerides the following is recommended:

- 20-25% of calories as fat,

- Monosaturates (olive oil and canola), and

- A handful of nuts (walnuts, hazelnuts) every day.

Doctors may also prescribe appetite stimulating and anabolic agents. Exercise should be encouraged to increase the patient's strength/muscle mass and referral to a physical therapist may be necessary.

Social workers can assist to ensure that the client has access to a safe and nutritious supply of food and that the members of the healthcare team continue to work together to improve the quality of life of the person who is HIV/AIDS positive.

Nutritional Information

Nutritional Information

HIV/AIDS Prevention

How Can I Prevent HIV/AIDS?

The most common way people are infected with HIV is by having sex with an infected person. You can't tell by looking at a person whether they have HIV, so you have to protect yourself -- and your sex partner.

Safe Sex and HIV Prevention

• Don't have unprotected sex outside marriage or a committed relationship. If you or your partner has ever had unprotected sex -- or if either of you uses injected drugs -- the only way to be sure you don't have HIV is to get tested. Have two HIV tests six months apart, with no new sex partners or injection drug use between tests.

• You can't get HIV if your penis, mouth, vagina, or anus doesn't touch another person's penis, mouth, vagina, or anus. Kissing, erotic massage, and mutual masturbation are safe sex activities.

• You can greatly reduce your risk by using a latex or polyurethane condom during sex. Don't use natural-skin condoms -- they prevent pregnancy, but they don't prevent infections. Put the condom on as soon as you or a male partner has an erection, not just before ejaculation. Use a lubricant -- but never use an oil-based lubricant with a latex condom. The female condom, called a vaginal pouch, also protects against disease.

• Oral sex without a condom or latex dam is not safe, but it's far safer than unprotected intercourse.

• The HIV drug Truvada has been approved for use in those at high risk as a way to prevent HIV infection. It's to be used in conjunction with safe sex practices.

Drug Use and HIV Prevention

Using drugs increases your HIV risk. If you're not ready to stop taking drugs, you can still reduce your risk of getting HIV/AIDS. Here's how:

• Don't have sex when you're high. It's easy to forget about safe sex when you're on drugs.

• If you use drugs, don't inject them.

• If you inject drugs, don't share the equipment. This includes every piece of it: needles, syringes, cookers, cotton, and rinse water. Some states have needle-exchange programs where you can trade in dirty equipment for new equipment.

Pregnancy and HIV Prevention

Mothers with HIV can give the virus to their infants during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding. If you're pregnant, get an HIV test. Anti-HIV drugs taken during pregnancy and delivery can greatly reduce the risk of passing the virus to your baby. If you have HIV, feed your infant formula or breast milk from an uninfected woman.

Blood Contact and HIV Prevention

Although transmission is rare, you can be infected by HIV from contact with the blood of an infected person. If you're helping a bleeding person, be careful to avoid getting his or her blood into any cuts or open sores on your own skin -- or in your eyes or mouth. If possible, wear gloves and protective eyewear.

Video - Cumulative Review

Video - Cumulative Review

References and Useful Web Sites

- AIDS Info Net fact sheet 2007: Number 156 - www.aids.infonet.org AIDS/Meds.com.

- Trizivir - http://www.aidsmed.com/drugs AIDS/Meds.com.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS statistics and surveillance: basic statistics. - http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics

- CDC Fact sheet: Estimates of New HIV Infection - http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/fact sheets/incidence_overview.htm. CDC.

- HIV Prevalence Estimates. MMWR, 2008; 57:1073-1076. - http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/basic.htm. CDC.

- OraQuick rapid HIV test for oral fluid-frequently asked questions. Retrieved CDC. (2003b).

- HIV/AIDS Among African Americans - http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/facts/afam.htm. CDC. (2003c).

- HIV and its treatment: What you should know (2nd ed.). Center for Disease Control, National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention, Divisions of HIV/ AIDS Prevention. - http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/adult/brochure/. Goldrick, B., Baigia, J., Larsen, J., & Lemert, J. (2000).

- Nursing research and HIV infection: State-of –the-science. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 32(3), 233-238. Proquest. Hall HI, Ruiguang S, Rhodes P, et al

- Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008; 300:520-529. HIV Surveillance 2010 Update - http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/facts/afam.htm. Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen R.

- Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USAA. AIDS. 2006; 20:1447-1450 - http://aidsonline.com/pt/re/aids/fulltext Pinkerton, S., Martin, J., Roland, M., Katz, M. et al. (2004).

- Cost-effectiveness of post exposure prophylaxis after sexual or injection-drug exposure to human immunodeficiency virus. Archives of Internal Medicine. 164(1). P 46-56. Retrieved CDC. (2003b).

- HIV disease susceptibility in women and the barriers to adherence. Medsurg Nursing, 13(2), p13 (2), p 97-105. Retrieved July 27, 2015 from Proquest 13(2), p 13(2), p 97-105.

- UNAIDS Epidemic Update 2010 Retrieved July 27, 2015 from http://www.unaids.org

- UNAIDS Epidemic Update 2008 Retrieved July 27, 2015 from http://www.unaids.org

- HIV/AIDS CEU Activity - https://www.ceufast.com/course/aids-hiv-4hr/#sthash.WAYUbGGP.dpuf

Cumulative Review Quiz

.

We are surrounded by billions of bacteria and viruses. To many of them, a human being is like a walking smorgasbord, offering nearly limitless resources that they can use for energy and reproduction. Luckily for us, getting into the human body is not an easy task!

We are surrounded by billions of bacteria and viruses. To many of them, a human being is like a walking smorgasbord, offering nearly limitless resources that they can use for energy and reproduction. Luckily for us, getting into the human body is not an easy task!