The Questionnaire Development Process

Most marketing researchers follow the following 10-step process when developing questionnaires:

Step 1: Determine the Survey Objectives, Resources, and Time Constraints

Once the decision has been made to conduct a survey, the marketer and marketing researchers must agree on the survey objectives, or what information the survey is to collect. In addition to establishing the goals of the survey, a budget and timetable must be established.

Step 2: Determine How The Questionnaire Will Be Administered

As previously stated, marketing researchers can administer surveys in a variety of ways. Researchers administer surveys online, through the mail, on the telephone, or by face-to-face interviews. Each method has its strengths and weaknesses:

Face-to-Face Interviews

Face-to-face interviews were once the most commonly used method of administering surveys. Seventy years ago it was not uncommon for interviewers to visit neighborhoods and knock on potential respondents doors. When researchers administer a questionnaire with a face-to-face interview they now use mall-intercept interviews. Mall-intercept interviews are conducted at shopping malls. The interviewer approaches a shopper who appears to meet the definition of the desired respondent. After the interviewer determines that the potential respondent is an appropriate respondent, the interview can be given on the spot or the person is invited to a facility located in the mall to complete the questionnaire.

Mall-intercept interviews are very popular. It is estimated that nearly two-thirds of marketing research questionnaires are completed at shopping malls.[1] Mall intercept interviews are especially appropriate when the research needs to show stimuli or demonstrate things. They allow researchers to conduct taste tests and use visual stimuli. The disadvantages are than mall-intercept interviews are expensive, they are limited to metropolitan areas, and they may not be demographically representative of the population of interest. Mall-intercept interviews may over-represent young women, people who live in the suburbs, people with middle incomes, and frequent shoppers. Another problem with mall-intercept surveys is that malls may not be the most comfortable location for people to answer questions and this may limit the ability to capture the respondents attitudes.

Telephone Surveys

A telephone survey is another method of survey administration. With this method, potential respondents are contacted by telephone. The phone numbers are selected using a random dialing system or other computer techniques designed to ensure the random selection of the respondents and the most likely time to reach them at home. This method is commonly used in public opinion surveys. Telephone interviews have a high response rate and the researchers can ask follow-up questions. They are, however, expensive to conduct. A disadvantage of telephone surveys is that the research cannot use visual stimuli.

Mail Surveys

For mail surveys, the questionnaires are delivered through the mail. Market researchers use two types of mail surveys: Ad Hoc Mail Surveys and Mail Panels. These questionnaires are self-administered by the respondent; which is to say, there is no interviewer.

With ad hoc mail surveys, questionnaires are mailed to random people with whom the researchers have no relationship. These names may have been acquired through purchased mailing lists. The marketing researchers contact these potential respondents once. Mail panel surveys are composed of respondents who have been pre-screened. Members of the mail panel have agreed to participate in regularly administered surveys.

Despite having to pay for postage to and from respondents and the cost of printing of the questionnaires, mail surveys are relatively inexpensive to conduct. But, mail surveys take a long time for responses to come back to the researchers and the response rates can be low. Non-responders are typically not evenly distributed among the sample. Respondents with high income and high education levels tend not to complete mailed surveys. This unequal distribution of non-responders can bias the results.

Online Surveys

Self-administered surveys delivered through the Internet are rapidly growing. They offer advantages, which many researchers think outweigh some serious disadvantages.

Among the advantages of online surveys are:

- Rapid deployment of the questionnaires

- Rapid analysis of the results: Respondents perform the data entry for the researcher. This saves time and money. Online surveys often use software that can summarize the results. And, data from online surveys can be automatically imported into statistical programs like SPSS and database programs like Microsoft Access.

- Reduced cost: With no printing and postage, Internet surveys are far less expensive than mail surveys. And, tabulating the results of an online survey is much faster and less expensive than telephone surveys.

- Higher response rates than mail or telephone surveys: Online surveys are faster to complete than telephone or mail surveys, which lead to higher response rates.

The disadvantages of online surveys include:

- Sample Bias: Internet access is still not universal. This raises the issue of whether online surveys represent the population of interest. This is a problem because the researchers cannot be certain of the demographics, psychographics, and usage patterns of the person completing the survey.

- Measurement Error: Research suggests that online surveys may have low reliability and validity. These concerns stem from studies that administered the same questionnaire online and offline with significantly different results. [2]

- Non-Response Bias: Respondents who answer online questionnaires have very different demographics and attitudes than those who do not respond. [3]

- Response rates: Response rates for online fall sharply when questionnaires exceed 15 questions. [4] At present, expert opinion suggests that online surveys should take no longer than 7 minutes to complete.[5] A 5 to 7 minute survey typically has between 11 to 15 questions.

Step 3: Determine the Question Format

Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions are like the questions used with Exploratory Research. Respondents answer the question using their own words. Open-ended questions to not contain a set list of answers.

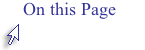

Here is an example of an open-ended question:

Figure 1

Many questionnaires end with an open-ended question. Here is an example of such a question:

Figure 2

Open-ended questions are much more difficult to edit and code than closed-end questions. Editors must carefully review and categorize the answers for each open-ended question. And, just like the open-ended questions asked in focus groups, the interviewer probes—requests more information from the respondent—to derive full meaning from a response. Probing means asking follow-up questions like, "What did you mean by that?" and "Could you tell me more about that?" Probing can be done with questionnaires administered using face-to-face interviews. But, this takes more time for the interviewer to complete the interview. Probing open-ended questions are thought to have higher interviewer bias than closed-ended questions. Interviewer bias occurs when a respondent consciously or unconsciously modifies his or her answers due to the social style and personality of the interviewer.

Closed-Ended Questions

Most questions posed in questionnaires are closed-ended questions. Closed-ended questions provide the respondent with a fixed list of answers. Closed-ended are easier and faster to code. Interviewers with less skill can easily handle closed-ended questions. And, interviewer bias is less likely with closed-ended questions. On the other hand, these questions may lack an adequate range of responses. And, if poorly phrased, they could introduce bias.

There are three basic categories of closed-ended questions:

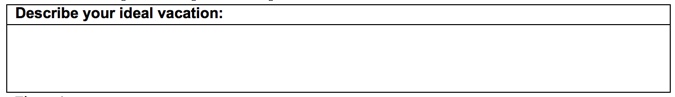

1. Dichotomous Questions

The simplest form of closed-ended questions is the dichotomous question. Dichotomous questions ask the respondent to select from two possible answers. Here are some examples:

Figure 3

These questions are considered categorical questions. They generate nominal level data as the answers are not numerical and no order is implied. Nominal data merely places the respondents' answers in one of the listed categories. These categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. The term mutually exclusive means that any possible answer fits in only one category. No one, for example, can answer that they have a pet dog and they do not have a pet dog. Exhaustive means that the provided list of responses covers all possible answers. Please Note: the question on gender is how such questions have been posed historically. With the heightened awareness of the fluidity of gender, many researchers no longer ask questions about gender using dichotomous questions.

2. Multiple-Choice Questions

There are two forms of multiple-choice questions: Multiple-Choice and Multiple-Answer.

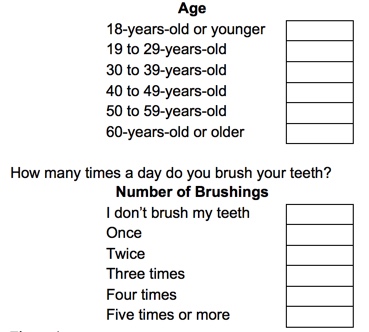

Multiple-Choice Questions: With multiple-choice questions, respondents select one answer from a list of three or more options. Here are some examples of multiple-choice questions:

Which of the following age groups are you in? Check the appropriate box:

Figure 4

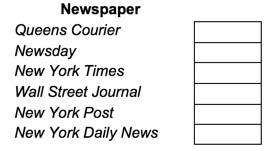

Multiple-Answer Questions: Multiple-answer questions are a type of multiple-choice question that allows respondents to provide more than one answer. These questions are sometimes called checklist questions as the respondent can check off multiple answers from a list of options. Here is an example of a multiple-answer question:

Which of the following newspapers to you read regularly? Check all that apply.

Figure 5

3. Scaled Response Questions

Scaled response questions are designed to capture the intensity of a respondent's feelings and attitudes. We covered numerous forms of scaled response questions in the Measurement module. These scales include:

- Graphic Ratings Scales

- Itemized Ratings Scales

- Semantic Differential Scales

- Stapel Scales

- Likert Scales

For a discussion of these response scales please read the lesson on Measurement.

Step 4: Writing Clear Questions

1. Questions must be clearly written, easily understood, and unambiguous.

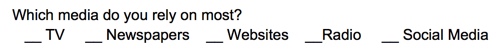

Good questions are written using proper grammar. They are simply worded. Avoid jargon. Precision is important. Take a close look at the following question. Can you see why it is a poor question?

Figure 6

This is a bad question because the context for "rely on most" is undefined. What are we talking about? Sports? Entertainment? Restaurant Reviews? News? This question needs to be rewritten so that the context is clear.

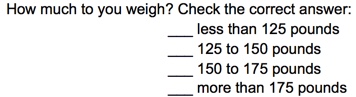

What is wrong with this question?

Figure 7

The problem with this question is that the responses are not mutually exclusive. Suppose a respondent weighs 150 pounds. He could select 125 to 150 pound and 150 to 175 pounds. The answers overlap. They must be mutually exclusive.

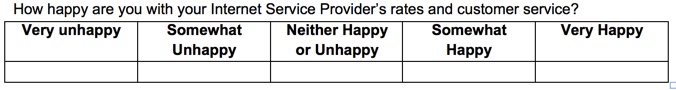

What is wrong with the following question?

Figure 8

This is what we call a double-barreled question. The problem with double-barreled questions is that they are really asking two questions. They confuse respondents and it is impossible for the researcher to know if the respondent's state of pleasure refers to the ISP's rates or customer service or both. Never use a double-barreled question. A good researcher would pose two questions: one on rates and another on customer service.

2. Questions must not introduce bias.

Researchers can introduce bias by asking leading questions, loaded questions, or imposing opinions on the respondent.

Leading questions introduce bias because they implicitly suggest a particular answer.

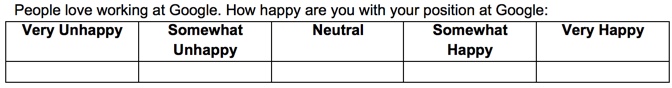

Here is an example of a leading question.

Figure 9

Here is a better way to phrase this question:

Figure 10

The problem with the first version of this question stems from the words People love working at Google...." Leading questions often being with a statement like this one. This rpeface tends to dias the question because it implies the respondents share an attitude.

Loaded Questions:

Loaded questions ask emotionally charged questions or offer a socially desirable answer. They contain unnecessary assumptions that can distort a respondents answer because they make presumptions about the respondents attitudes, beliefs, or behavior.

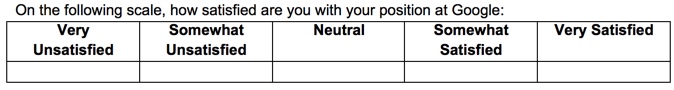

Here is an example of a loaded question[6]:

Figure 11

This question should be rewritten to remove the emotional charge.

Figure 12

3. Imposing Assumptions:

Good questions do not impose value judgments on the respondent. The following question makes an assumption that could distort responses.

![]()

Figure 13

The problem with this question is the inclusion of the word "excellent." That word imposes a value judgment that respondents might not share. Good researchers never impose value judgments on respondents as they introduce bias.

4. Respondents' Ability to Answer

Problems can occur when researchers ask questions that the respondents are not qualified to answer. Here is an example of a question that smart phone users are most likely not qualified to answer and probably have no strong opinions: Should Apple Inc. change the supplier of processors it uses in its iPhones?

Good researchers always consider the respondent's qualifications for answering a question.

Questions should avoid taxing a respondent's memory. People forget. This is a simple fact:

Advertising recall tests are designed to see if television viewers remember commercial. Typically these tests are conducted 24-hours after a commercial airs. A 24-hour delay does not tax respondents' memories. The research company calls potential respondents, and the interviewer takes two measurements: unaided recall and aided recall. Here is how the researcher might ask the questions if the client were Diet Coke and the commercial ran on The Simpsons.

![]()

Figure 14

If the respondent answers "yes," ask the following question:

Do you recall any of the brands advertised on this program?

The researcher records the names of the brands. If a respondent can identify a brand, this is called unaided recall.

If the respondent does not have unaided recall of the Diet Coke commercial, ask: Do you recall seeing any commercials for a carbonated soft drink? If the respondent can recall the Diet Coke commercial, this is aided recall.

With events that are in the more distant past, people may have a poor recollection of when the event actually occurred or other details of the event. Two different phenomena threaten the validity of the response. Telescoping is when a respondent thinks an event happened more recently than it actually occurred.[7] Squishing occurs when a respondent thinks that an event happened longer ago that it actually did.

5. Respondents' Willingness to Answer

Sometimes a respondent's memory is very clear, yet they do not want to answer a question if brings up potentially painful or embarrassing memories. Questions about bankruptcy, divorce, sexual activity, sexual harassment, criminal activity, and health issues fall into this category.

To relieve the respondent of their embarrassment, researchers often preface a potentially embarrassing question with a counterbiasing statement.

Consider the following question: "Where your parents married to each other when you were born?" Being a child born out of wedlock is a source of embarrassment for some people. Many researchers would add a counterbiasing statement to this question: Here is how they might rephrase this question: "Many people are born to parents who were not married to one another at the time of their birth. Were your parents married to each other when you were born?"

Step 5: Designing the Question Flow

Not only do researchers spend a lot of time writing and rewriting each question, they also must devote considerable thought to the logical flow of the questions. When considering the flow of the questions, researchers want to make certain that they:

- Avoid responses from unqualified respondents

- Make respondents feel confortable so they answer the questions honestly

- Ask questions that provide all the information they need

Many researchers organize their questionnaires into six parts:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Initial Screening of respondents

Part 3: Warm-up questions

Part 4: Transition into more detailed and more difficult questions

Part 6: Farewell

Part 1: IntroductionAll questionnaires need an introduction. This is especially true if an interviewer administers the questionnaire.

The introduction is designed to gain the trust of the potential respondent. Good introductions:

- Provides the interviewer's name and the name of his or her employer

- Tells the respondents the subject of the interview

- Assures the respondent that he or she will not be sold anything and that their privacy will be protected

- Tells the respondent how long the survey will take to complete

- If applicable, have the respondent sign a consent form

- Invites the respondent to complete the survey

Here is a sample of an introduction:

"Hello, my name is Edward Volchok and I am with ABC Consumer Surveys. Today we are asking people at the Roosevelt Field Mall about their dogs and the treats they give them. This interview will last about 12 minutes. We would very much appreciate you taking the time to answer a few questions. Do you want to participate in our survey?"

If the respondent agrees, the interviewer might have them sign a short consent form and then proceed with the interview. If the respondent declines, the interviewer will smile and thank them for their consideration.

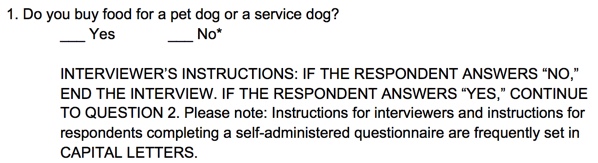

Part 2: initial Screening of RespondentsNot everyone who is approached to complete a questionnaire is qualified. To avoid surveying unqualified respondents, researchers begin their questionnaire with a screener or filter question. Screener questions are designed to filter out unqualified respondents. A questionnaire can use just one screener question or many. The more screener questions, the longer it will take to complete the survey and the more expensive it will become.

Here is an example of a screener question for a questionnaire for a marketer of gourmet dog treats.

Figure 15

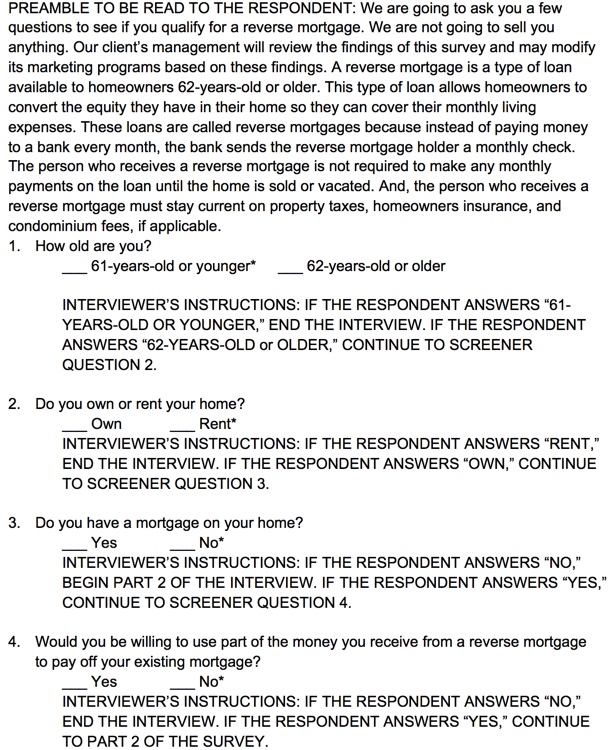

Here are four screener questions for a questionnaire targeting people 62-years-old or older. The client is a marketer of reverse mortgages. The client, therefore, is not interested in people who are not at least 62-years-old or individuals who a do not have significant equity in their home.

Figure 16

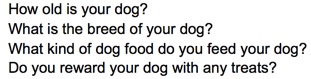

Part 3: Warm-Up Questions

After the screener questions, the respondent moves to Part 2 of the questionnaire. In this section, researchers focus on general questions. Asking general questions before specific questions is sometimes called the funnel technique. The goal of the research in part to is to "warm up" the respondent. Tough questions and questions that can cause embarrassment are saved until the end of the questionnaire. Asking questions about sensitive subjects like age, income, and sexual orientation, are typically avoided in the early phases of the questionnaire. Our reverse mortgage, however, does ask sensitive questions about age and finances. To soften these screener questions, we gave respondents a review of what a reverse mortgage is. This review implies that the screener questions are necessary.

Here are a few examples of warm-up questions for people who buy dog food:

Figure 17

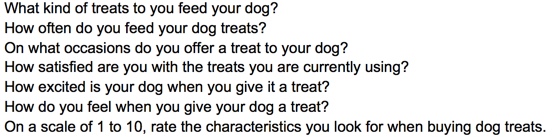

Part 4: Transition Into More Detailed Questions

With part 4, the questionnaire makes the transition into questions that relate to the research objectives. These questions are more detailed and often use a ratings scale.

In the case of our questionnaire on the treats dog owners give their dogs, we might focus on the following questions:

Figure 18

Part 5: Demographics, Psychographics, Usage Behavior And Questions That Might Cause Embarrassment

Researchers generally place questions at the end of the questionnaire that might cause a respondent to stop an interview because the it is seen as too intrusive or embarrassing. Researchers do this to collect usable data before a respondent might halt the interview. The other reason to place such questions at the end of the survey is that respondents may have developed a rapport with the interviewer and they may have become accustomed to answer the questions.

Many researchers argue that the end of the questionnaire is an ideal place for collecting the respondent's demographics, psychographics and usage behavior. But not every researcher agrees. As we saw with our examples of screener questions, we might need to collect some demographic, psychographic, and usage behavior information to filter out unqualified respondents.

Part 6: Farewell

At the end of an interview, the interviewer or the questionnaire itself )if the research is using a self-administered questionnaire), bids farewell to the respondent. The farewell statement thanks the respondent for their time, tell the respondent that his or her opinions count, and express the hope that the interview was a good experience. Here is a standard farewell statement.

"The survey is now complete. I hope you found this experience pleasurable. Thank you for sharing your opinions. It is only by listening to people like you that our clients can bring better products to market."

Some Tips to Limit Bias

We have reviewed a number of problems that can undermine a questionnaire: Questions that are too complex, too vague, or lack context, leading questions, loaded questions, and double-barreled questions. Researchers also use the following techniques when developing effective questionnaires:

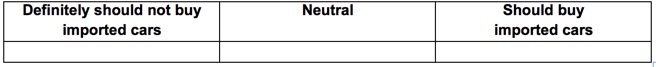

1. Split Ballot Technique

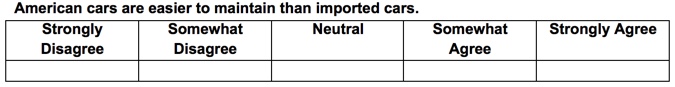

With the split ballot technique the researcher uses two versions of a question. Half the respondents get one version and the other half get the second version. Using two alternative phrasings of same question administered to respective halves of the sample reduces bias from potentially loaded questions. Here is a question asked in two ways:

Version 1

Figure 19

Version 2

Figure 20

2. Avoiding Order Bias

Order Bias: Order bias results when a question affects respondents' answers to questions that follow.

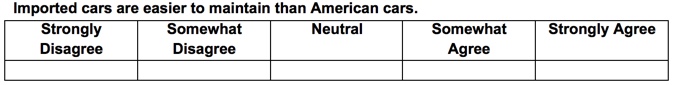

Order bias can result from the order of answers. Let's look at the following multiple-choice question:

Figure 21

Respondents tend to select the first or last item on the list. Researchers rotate the list of the first four answers so that Coffee is not always at the top of the list. Some methodological research suggests that the some respondents are more likely to select the first item on the list of answers.

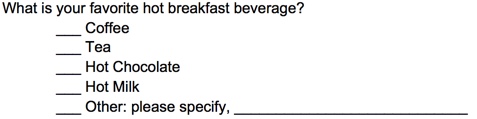

Branching and Filter Questions

We seen how filter questions are intended to stop a respondent who is unqualified to answer a question. Filter questions are also used to direct respondents to answer alternative questions. This process is called branching. Here is an example of branching.

Figure 22

Step 6: Questionnaire Evaluation

At this stage, the questionnaire goes through its first evaluation. Researchers focus this evaluation on three questions:

Question 1: Is this question necessary?

Once there is a rough draft of the questionnaire, researchers and their clients use their judgment to review the questionnaire. An essential part of the process is to eliminate redundant questions. One researcher I worked with used to say about questionnaires that you "start fat, and work to get thin." What he meant is that you write a lot of questions and then you start to eliminate many of them.

Each question must serve a purpose. Questions must relate directly to the survey objectives. If a question does not have a strong link to the survey objectives, the researchers consider eliminating it.

Question 2: Is the questionnaire too long?

If a questionnaire takes too long to complete, it will not be effective. Researchers often play the role of respondent to determine how long it takes to complete the questionnaire. Questionnaires administered online should take respondents about five minutes to complete, and in no case should it take longer than seven minutes. Questionnaires administered on the telephone or using mall-intercepts should take less than 20 minutes to complete. These surveys may be longer if respondents are told that they are going to be compensated with a valuable premium once they complete the questionnaire.

Question 3: Will the questionnaire provide all the needed information?

Researchers link each question to a survey objective to ensure that the questionnaire meets its objectives.

Step 7: Obtain Client Approval

Market researchers must service their clients. The hallmark of good client service is keeping clients in the loop. In the case of questionnaire development, getting all parties who have decision-making authority to approve the questionnaire is a critical step. If the questionnaire cannot get approval, it must be revised or the entire project must be reconsidered.

Step 8: Pretest and Revise the Questionnaire

Researchers can reexamine many of the questions raised in Step 6 by testing the questionnaire using a small sample. During this phase of the process, researchers want to determine whether respondents find any part of the survey confusing, unclear, or boring. The pretest should be conducted among the same type of respondents as the final questionnaire. And, the pretest should use the same survey administration method.

Step 9: Prepare Final Questionnaire Copy and Layout

At this stage, the researchers review the results of the pretest and revise the questionnaire, if necessary, based on the results of the pretest. The final layout of the questionnaire should be developed for the selected administration technique. The final questionnaire copy and layout will be presented for client approval.

Step 10: Field Questionnaire

With the approval of the questionnaire's final copy and layout, it is time to field the questionnaire; which is to say, conduct the survey. To do this, the researchers hire a field service firm. This firm distributes the questionnaires among the respondents, collects the results, verifies the results, and delivers the raw data to the researchers.

The researchers gives the field service firm instructions on how to conduct the survey. These instructions are placed in a written document called supervisor's instructions. This document:

- Summarizes the objectives of the survey

- Provides information on the survey administration

- Details the timeframe when the survey must be completed

- Specifies the number of respondents to be interviewed

- Details the number of questionnaires to be provided

- Outlines the number of interviewers required

- Provides other necessary instructions

Once the field service firm delivers the raw data, the researchers analyze the results and report their findings to the client.

[2] Sax, L. J., Gilmartin S. K. and Bryant A. N. (2003). "Assessing response rates and non response bias in web and paper surveys," Research in Higher Education, 44, 4, 409-431. Carini, R. M., Hayek, J. C., Kuh, G. D., Kennedy, J. M. and Ouimet, J. A. (2003) College students responses to web and paper based surveys: Does mode matter? Research in Higher Education , 44, 1, 1-19. Umbach, P. D. (2004). "Web surveys: Best practices," New Directions in Institutional

[3] Umbach, P. D. (2004). "Web surveys: Best practices," New Directions in Institutional Research, 121, 23-38. Bosnjak, M. Tuten T. L. and Bandilla W. (1991) Participation in web surveys: a typology, ZUMA Nachrichten, 48, pp. 7-17.

[4] Witmer, D. F. Colman, R. and Katzman, S. L.(1999). "From paper-and-pencil to screen-and-keyboard: Towards a methodology for survey research on the Internet, in Jones, S. (Ed.) Doing Internet Research: Critical Issues and Methods for Examining the Net. London. Sage. pp. 145-161.

[5] https://www.surveymonkey.com/blog/2011/02/14/survey_completion_times/

[6] Neuman, W. L. (2007).Basics of social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches(2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

[7] Paul J. Lavrakas, (2008). Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods, http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/encyclopedia-of-survey-research-methods/n579.xml

toc | return to top | previous page