Unit II: Education

Copyright Phillip Roncoroni "Ideas are Bullet Proof: Occupy Wall St"

QUEENSBOROUGH COMMUNITY COLLEGE ARCHIVES PROJECT - Laurel Harris

We return to the archives to see for ourselves what has been left out, to retell the story, or to see the traces of a life, a historical event, an institutional history. What if we were to teach research writing through involving our students in the process of archival exploration? What if we were to invert the research process so that the task would not be one of synthesizing secondary sources, but, rather, one of contextualizing the primary sources simultaneously remembered and forgotten in the boxes of the archives? Bringing students into the archives can emphasize the organic and experiential, even the auratic, qualities of research. There are a wealth of digital archives that can be used in the writing and literature classroom. Online literary archives such as the Walt Whitman Archive and Modernist Journals Project and historical archives like John Jay's Crime in New York, 1850-1950 and Old Bailey Online, 1674 -1913 offer a treasure trove of primary sources to be interpreted and analyzed. However, my classroom project is a work in progress designed to make the dustiest of literacies--navigating physical archives--visible through online spaces, in the process offering our first-year writing students new possibilities for constructing and representing knowledge.

This project, still very much in-progress, was developed over two semesters through a partnership with the Queensborough Community College archivist Connie Williams . It involves community college students in the first-year writing classroom in the historiography of our college. My central goal through this process is to position students as interpreters of resources that have received little contemporary attention beyond the archives. In this reconstruction of the research paper, a genre generally relegated to the first-year writing program, I begin with the gap not only in my students' knowledge, but also the broader gap in campus and community knowledge, conduct background research, move into the archives, and, finally, reflect on the experience.

While I believe that research skills are one of the most important things I teach in first-year writing, I have long struggled with assigning the traditional research term paper, what Robert Davis and Mark Shadle call the "modernist term paper" with its "ideals of expertise, detachment, and certainty" (418). Nevertheless, I have found that the large-scope research project promotes crucial habits of mind. From the perspective of someone trained in literary research, I still maintain that research enables readers to enter the room and join the conversation to use Kenneth Burke's famous metaphor, promoting living in and through texts, becoming part of them. This is how research differs from search, which involves simply finding information while research requires sifting, interpretation, and synthesis. The Internet, I believe, has largely transformed the "modernist term paper" into an empty exercise, an invitation to right click plagiarism at worst.

The question becomes how to preserve key aspects of what we might call the traditional (as in early twentieth-century) research paper--participation in a larger academic conversation and information literacy--while making the work meaningful, not merely a formal exercise. Davis and Shadle call for a research process that values "uncertainty, passionate exploration, and mystery" (418). My theory in designing this project was that our campus archives might offer a rich repository for this focus on inquiry over mastery.

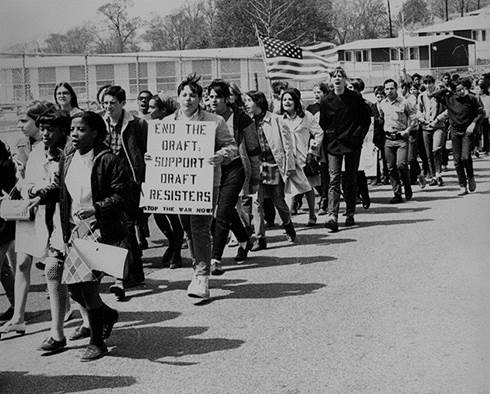

QCC Archive Photo, 1969 - Student War/Draft Protest March

I constructed this project using the college archives while teaching an English 101, introductory composition, course in a Learning Community, or shared class, with Sociology. In the Sociology section, students focused on texts about social unrest. In the English course, we applied this theory to student rebellion in the 1960s with a specific focus on a student occupation of the Queensborough administration building in1969, one of a series of student takeovers across New York City campuses in the spring of that year. While there were numerous articles that addressed this particular action at Queensborough in 1969, through the early 1970s in publications such as the The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The AAUP Bulletin, the only contemporary mentions I could find to bring to class appeared (very briefly) in Rick Perlsteins Nixonland (2000) and a chapter in former left-wing Queensborough history professor turned right-wing activist Ronald Radoshs memoir Commies (2001).

I will quote, with permission, a summary of what happened in 1969 on our campus from one of my student's papers: "A climb in tuitions and the removal of an English professor triggered a riot . . . The dismissal of Dr. Donald Silberman [allegedly for his leftist activism]. . . started it all. By 1969 roughly 8, 000 students attended QCC, and amongst them 50 pupils began a sit-in on the fourth floor of the administration building. Professor Silberman along with two of his coworkers, Professors Faigelman and MacDonald, joined them. The 50 pupils transformed into 300 striking students...[They] succeeded in that they made history, but failed because [50] students departed to jail and were kicked out of school. The professors were deprived of reappointment."

Such an action, specific to the Queensborough campus, had to be contextualized with student revolts that spring across other New York City campuses, (including Brooklyn College, City College, New York University, Fordham, and Columbia), for a multitude of reasons, including protested tuition increases, demands to admit more local students and students of color, and the push for black and Latino studies departments and research centers. We also considered the larger national context of student unrest, focusing on the Students for a Democratic Society's 1962 Point Huron Statement, the 1964 Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, and Angela Davis's 1969 firing from UCLA. After watching films and reading about these events in class, and writing informally in response to each text, students came up with their own research questions in groups in preparation for their visit to the college archives, including:

- Why did the protesting students care that the teachers weren't reappointed?

- How many students went to QCC in 1969? What is the ratio of students who protested to students who didn't join the protest?

- What did students who didn't protest think about the protests?

- How do the QCC protests connect to the other protests at New York City colleges that spring?

- What were the student s like in 1969? Were they different from students today?

- What was the role of media in the protests? How would it have been different if they had Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter then?

With these questions in mind, we visited the college archives, housed in the bowels of the library, over one week in two 100-minute sessions. In the first session, archivist Connie Williams gave an introduction to using the primary sources. Then she set the 25 students free in the archives, a tight, cool room full of boxes with an entire wall of old yearbooks, newspapers, course bulletins, and literary magazines on one end. In their reflections many students cited this as their favorite part of the project. They pulled the boxes labeled QCC Riots off the shelf and stacked them on the carts, then searched for other relevant materials including course bulletins, yearbooks, and newspapers from the period. Tightly packed back in another room around a long table, students began searching for the answers to their questions and formulating new questions, marveling at a yellowed sign protesting the institution of tuition and pouring through copies of the College Board hearing on the campus action. In their reflections, they acknowledged both the tedium and sense of discovery inherent to archival research. More than one student described it as being a detective. Their reflections expressed engagement in exploring the archives but considerable frustration in the search itself. Some students, hoping to find the answer key that eluded them in the boxes, told me that they had turned to the internet, especially Wikipedia, seeking some meaningful synthesis of this event that they could hook their ideas onto. Such a synthesis is not available online. One student asked the archivist if there were a book, an institutional history of Queensborough, available that she could read to contextualize her research. "There isn't a book about this history of Queensborough. You're going to have to write it," Prof. Williams replied.

This project took place over seven weeks. At its conclusion, students submitted portfolios that collected the following: ten one-page reflections and reading responses, ten pages of handwritten notes from the archives, at least three photographs or copies of archival artifacts, and a paper of at least five pages that summarized the events, offered a close reading of at least two archival artifacts in that context, and concluded with a reflection on how the Queensborough campus had changed since 1969. These tasks were constructed to incorporate expository, ethnographic, and reflective writing into a research project that would have meaning beyond the first-year writing classroom, showing students both the value of original research and the rhetorical complexities of making the past visible and meaningful.

The majority of the reflections evidenced student engagement in the experience of visiting the archives to "see for ourselves" while citing the difficulty of the assignment. Most of the students essays followed a progress narrative in which students in the 1960s had fought for their rights, which were now established as "We got change, " although a few connected the events of 1969 to student arrests at Baruch College that fall. While I think there is value precisely in the obscurity of this event, a history waiting to be written, balancing the basic demands of the project with a more sophisticated construction of meaning will be a next step, one which might involve an entire semester rather than half a semester. However, judging from the portfolios and reflections, this project did help students understand research more organically as the filling of a gap and more socially as a collaborative effort to curate, contextualize, and interpret a community's past. Sifting through local archives enabled students to experience research as a social, situated practice as opposed to a textually-based practice that primarily involves synthesizing the work of experts. We now need to work on connecting this past to our present.

Arguments making this connection might be forwarded through photographs, films, interviews, and sound recordings as well as through text. In its next iteration, we intend to move students from searching physical archives to constructing online archives, a process which might also transform from the argument-based research paper to other rhetorical modes such as description and narration as we consider audience and purpose.

I still have many questions around this project as it continues to develop: Which platforms would work best for presenting and contextualizing archival artifacts? How does a focus on what archivist Peter Carini calls "information literacy of primary sources" correlate to the web based literacies it is crucial for our students to develop? How can the second iteration of this project best be constructed to forge and reflect on this link? I end with questions rather than answers, reflecting the ethos of this project as one of inquiry and uncertainty.

To find a lesson plan, bibliography, and other materials, please click here.